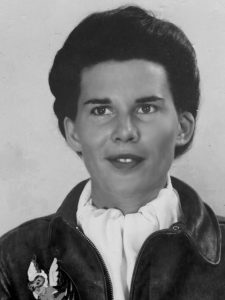

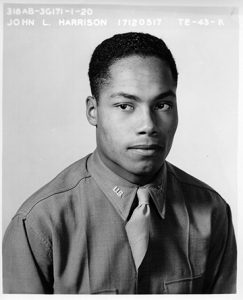

George Wyatt Porter

George Wyatt Porter

Sept. 19, 1921- February 9, 2013

Tuskegee Airman George Porter said the success of him and his comrades was due to hard work and, most importantly, not letting hatred get in the way of doing the job.

Porter entered the military in October 1942 and was selected to be a Tuskegee Airman at Tuskegee, AL, he was part of a group of 780 sent to flying school in Lincoln, Neb., and all 780 graduated.

“According to the history books, we made the highest score in history,” he said.

But it wasn’t easy.

He recalls the racism he and other black servicemen were subjected to, even as they watched enemy prisoners of war roam free on the base – including places they themselves weren’t allowed to go.

“We were on the base, but we could not go to the PX or the BX because we were black,” he said. “A guy walking around with POW on his back – prisoner of war – they could go anywhere.”

At times, some of the black servicemen wanted to go AWOL.

“We wouldn’t let that happen,” Porter said. “We helped one another.”

That spirit of cohesiveness was, according to Porter, integral to the success the Tuskegee Airmen experienced as they went to battle in Europe.

Initially given outdated P-40 Warhawks and relegated to secondary missions, Col. B.O. Davis lobbied Washington to issue the Tuskegee Airmen the same aircraft the white pilots were flying.

He finally succeeded, and the Tuskegee Airmen were given the new P-51 Mustangs and assigned to fly bomber escort missions.

“Each time they lost a bomber, they lost 10 men,” Porter said. He added that Davis instructed his pilots to stick with the bombers and not fly off and get killed trying to become an ace.

The hard work and strong leadership paid off, as the Tuskegee Airmen, flying their Mustangs with their distinct red-painted tails and nose cones, didn’t lose a bomber they were assigned to escort on the first three missions. Throughout the war, the unit had one of the best protection rates.

Porter himself passed flying school, but on his way out, a white medical officer pronounced that he had a restriction in his nose that wouldn’t allow him to fly at high altitudes.

After that, Porter became a mechanic, and he served in Tuskegee during the Second World War.

“I was the mechanic,” he said. “I worked from mechanic to crew chief to flight chief to line chief to flight line superintendent.”

After attending Airplane and Engine Mechanics School at Lincoln Field in Nebraska, Porter returned to Tuskegee Air Field as a crew chief and squadron inspector.

Porter also served as a flight engineer for the 477th Bombardment Group in 1945.

In a 2007 documentary, Porter spoke about the racial prejudice that made his job difficult during World War II.

“We did things that we weren’t supposed to do as the mechanics on the flight line. Because when we would order parts, they wouldn’t send us the parts, but we learned how to repair our own parts.”

The racism Porter experienced in the military was a new thing to him at the time. Raised in Louisiana, he said he grew up in part of a farming community where everyone worked together toward the common good. Even during the Great Depression, they managed to get by, as his uncles all worked at the sawmill or the brickyards for eight hours each day, then came home and plowed the fields.

He attributes the work ethic learned in his youth to his later success, eventually retiring from the Air Force as a senior master sergeant.

Porter stayed in the United States during World War II training pilots and crews on their way to combat. During that time, he fought an uphill battle with the supply depots trying to get the right parts to keep the aircraft flying.

“The government wouldn’t even send us parts down to Tuskegee,” he said. “We had to make them. We’d take the gallon cans tomatoes and fruits came in in the mess hall. We’d get the cans and cut the top and bottom off and cover holes in the planes.”

When President Harry Truman integrated the military in 1948, Porter was faced with racism, but he had a way of dealing with it.

“I had no difficulties,” he said. “I knew how to talk to guys. They’d come up to me and say, ‘Hey, boy, hey, boy, I wanna talk to you.’ I could have had them court-martialed and kicked out of the service, but every organization has a duty officer. I’d call the duty officer and have them put on the worst details.”

One of Porter’s favorites was to have a disrespectful man assigned to stand sentry duty at the end of the runway, “way out in the boondocks.” He said that, after a month of being stuck out there, the men would get the point, and they’d typically come back later and respectfully thank him for not having them dishonorably discharged.

“They’d say their parents taught them to call all black people ‘boy,’ ” Porter said. “I’d ask them how old they had to be to tell right from wrong.”

During his 45-year career, Porter was qualified to work on 22 aircraft, including the later B-52 bombers and KC-135 air tankers, and he circled the world twice.

Assigned to train new mechanics, he said he ran a tight crew. When aircraft were out on missions, he didn’t allow the mechanics time to relax and play basketball – he sent them to the library to pore over maintenance manuals.

Porter retired from the U.S. Military after 23 years of service in September 1965.

After moving to Sacramento, Porter worked for the United States Postal Service as a postal clerk. He later accepted a position at McClellan Air Force Base as an Aircraft Maintenance Management specialist. Even later he transferred to Aerojet General Corp.’s Engineering and Program Division as a logistic management officer.

A dedicated Tuskegee Airman, Porter once told a reporter that the Tuskegee Airmen’s story “should be in all history books.”

Watch a 2010 of Tuskegee Airman George Porter speaking to students.

SECC Vault: Tuskegee Airman George Porter (Elk Grove USD) By SECC EducationalTV

Sources:

MPR News

The Observer

Sacramento Observer

TAI Spanky Roberts Chapter