Training

At the end of 1938, the U.S. government sponsored the Civilian Pilot Training (CPT) Program, aimed at enhancing military preparedness with the goal of training 20,000 college students a year as civilian pilots. Initially, 11 colleges and universities were selected to participate in the program and provide pre-flight training.

The government paid for ground and flight school instruction, while the colleges provided instructors, physical examinations for potential students, and transportation to approved flying fields. The program also included opportunities for enlisted men and women to train for important non-flying support crew jobs. At its peak, 1,132 educational institutions and 1,460 flight schools were training potential pilots and support staff.

Alabama Hall at Tuskegee Institute.

In 1939, the program expanded to include the historically black and segregated colleges of Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University), Howard University, Hampton Institute, North Carolina A&T, Delaware State College, West Virginia State College and the Coffey School of Aeronautics, paving the way for black Americans to pursue military flight training. These schools would provide primary flight training for aspiring black pilots, but all other phases of training would take place at Tuskegee Institute, which was chosen for its history of training black civilian pilots, predictably mild weather suited for year-round flying, and a heavily segregated local population (a required condition for the program to operate). The Tuskegee cadets used the same flight school coursework as their white counterparts who were training at other bases, but were segregated at Tuskegee.

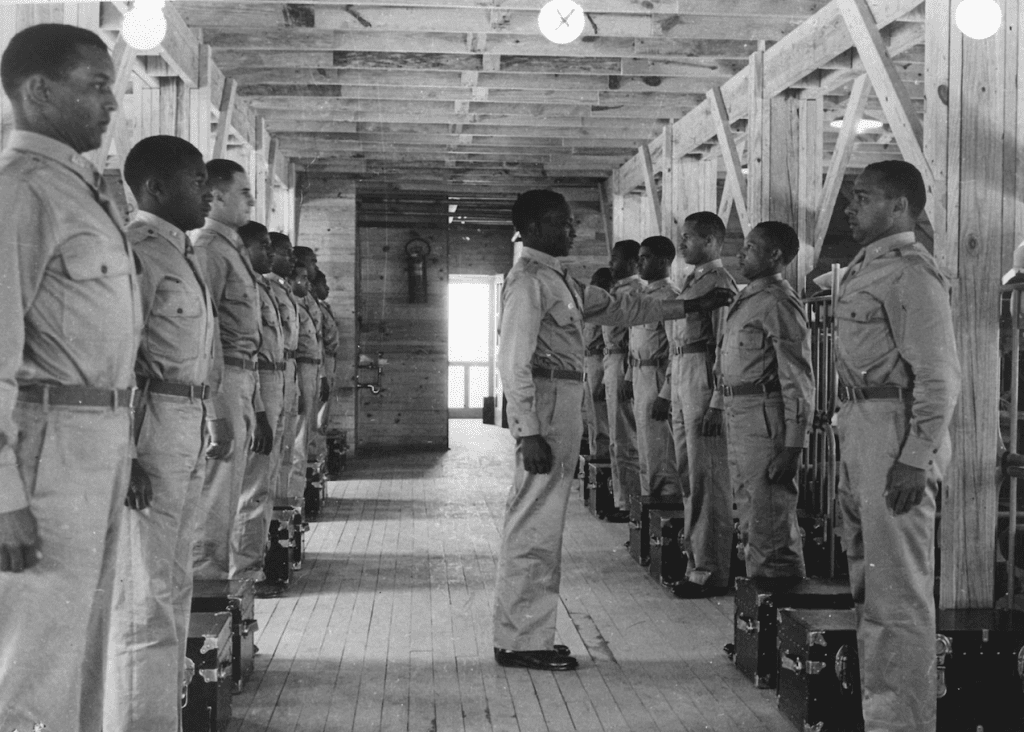

Further flight training for all CPT programs was provided at partnering private flight schools, with the black cadets being segregated to Tuskegee. Cadets would be required to pass primary, basic, and advanced flying training, and would be commissioned as officers in the U.S. Army Air Corps. Each phase was generally nine weeks long. Graduates would then proceed to transition training to learn to fly specific aircraft for the war effort.

Support personnel were trained at Chanute Field in Illinois.

Pilots trained at Tuskegee were primarily trained to fly fighter aircraft, but then expanded to include bombers, although the bomber group and its four squadrons did not deploy before the end of the war so their service was not needed overseas.

First graduating class of pilots in U.S. Army Air Corps Advanced Flying School in Tuskegee, Alabama. L-R: George S. Roberts, Benjamin O. Davis, Charles H. DeBow, R.M. Long, Mac Ross, and Lemmel R. Curtis.

In the spring of 1942, the first five candidates completed advanced pilot training at Tuskegee. The cohort included Benjamin O. Davis Jr., the first black American to solo an aircraft as a U.S. Army Air Corps officer, who would go on to lead the Tuskegee Airmen and become the first African American general of the United States Air Force. This first class was one of many who would rise above racism and prejudice to serve as our nation’s first black military pilots.

Rigorous training in subjects such as meteorology, navigation, and instruments was provided in ground school. Successful cadets then transferred to the segregated Tuskegee Army Air Field to complete Army Air Corps pilot training. The Air Corps oversaw training at Tuskegee Institute, providing aircraft, textbooks, flying clothes, parachutes, and mechanic suits while Tuskegee Institute provided full facilities for the aircraft and personnel. Lt. Col. Noel F. Parrish, base commander from 1942-46, worked to lessen the impact of segregation on the cadets.

Many cadets got their primary flight instruction at Moton Field, Tuskegee, from Charles A. “Chief” Anderson. The first class of five African-American aviation cadets earned their silver wings to become the nation’s first black military pilots in March 1942.

Upon graduation from advanced military flight training, the pilots were assigned to the 99th Fighter Squadron, the first black military flight squadron ever activated. By the end of the program, 44 classes of pilots graduated from the training program at Tuskegee. Although some cadets got their start in the CPT program before the advanced flight training at Tuskegee, not all future airmen needed to attend CPT before beginning primary flight training at Tuskegee.