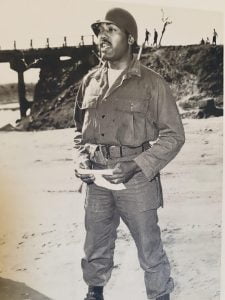

Charles Bussey

Charles Bussey

April 23, 1921 – October 26, 2003

Class: 43-E-SE

Graduation date: 5/28/1943

Rank at time of graduation: 2nd Lt

Service # 0804548

Unit: 332nd Fighter Group

From: Los Angeles CA

“His mother worried about the danger of his flying,” Mr. Bussey’s brother, Edmund, wrote in a eulogy. “He solved that problem by sending her an airline ticket and insisted that she fly to graduation when he received his silver wings.”

Charles Bussey was born in Kern, CA., and grew up in Bakersfield, California. After graduating from high school, Bussey attended Los Angeles City College for two years before enlisting in the military at the age of twenty.

Bussey was assigned to fly with the all-Black Tuskegee Airmen tasked to defend US bombers during World War II. His commander General Benjamin O. Davis Jr., played a big role in shaping Bussey as a soldier. Following World War II, Bussey left the Army and returned to Los Angeles, where he became a policeman. He didn’t like the work and decided to return to college by enrolling at San Francisco State University. After graduating from SFSU in 1948, Bussey rejoined the Army and was eventually stationed in Japan on occupation duty.

On May 26, 1950, Bussey took command of the 77th Engineer Combat Company in Gifu, Japan. The 77th Engineer was an all-Black unit that provided engineer support to the all-Black 24th Infantry Regiment. The 24th Infantry was the only all-Black subordinate unit of the 25th Infantry Division commanded by Major General William B. Kean.

On May 26, 1950, Bussey took command of the 77th Engineer Combat Company in Gifu, Japan. The 77th Engineer was an all-Black unit that provided engineer support to the all-Black 24th Infantry Regiment. The 24th Infantry was the only all-Black subordinate unit of the 25th Infantry Division commanded by Major General William B. Kean.

On July 20, 1950, Captain Bussey delivered mail to a platoon in his company stationed in the Korean village of Yecheon during the Korean War. Along the way, he heard rifle files from the village further up the road. Bussey stopped his vehicle and walked up a small hill that overlooked the village. Captain Bussey saw from his elevated position men dressed in white trying to outflank his men in the village. Bussey ran down the hill and rounded up three truck drivers from another unit parked near the hill. Lieutenant Bussey and his charges, armed with only a .50-caliber machine gun and a .30-caliber machine gun, are credited with killing 258 enemy soldiers.

After the battle, Bussey states he was told by a white officer he served under, Lt. Col. John T. Corley, that he would not receive a Medal of Honor for his efforts because “the country did not need another Jackie Robinson.” Reflecting on his heroic service to a country still shackled by segregation, this Silver Star hero later wrote, ‘I loved my country for what it could be, far beyond what it was.’ Lieutenant Colonel Bussey, thank you for helping America to realize what it could be and taking us beyond what we were.”

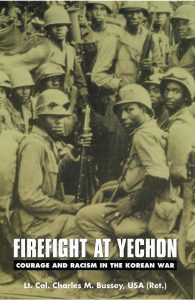

After the Korean conflict hostilities ended with the armistice of July 1953, Mr. Bussey was assigned back to Europe and was posted in Berlin, when the Berlin Wall was erected in August 1961. Mr. Bussey’s final Army assignment was from 1963 to 1966 at the Presidio of San Francisco. He retired from the US Army in 1966 as Lieutenant Colonel. He would work the next 20 years as a construction consultant before retiring and beginning work on his book about his wartime experiences, Firefight at Yechon: Courage and Racism in the Korean War. Bussey’s book was published in 1991.

After the Korean conflict hostilities ended with the armistice of July 1953, Mr. Bussey was assigned back to Europe and was posted in Berlin, when the Berlin Wall was erected in August 1961. Mr. Bussey’s final Army assignment was from 1963 to 1966 at the Presidio of San Francisco. He retired from the US Army in 1966 as Lieutenant Colonel. He would work the next 20 years as a construction consultant before retiring and beginning work on his book about his wartime experiences, Firefight at Yechon: Courage and Racism in the Korean War. Bussey’s book was published in 1991.

In 1967, Mr. Bussey started an African American-owned and operated business in Hunters Point that refinished furniture. The firm, called Patimik, also had contracts to clean phone booths and make crates for shipping war materiel to Vietnam. In 1969, Mr. Bussey was appointed to San Francisco’s Juvenile Justice Commission.

In 1994 a campaign was launched to try and upgrade Captain Bussey’s Silver Star for his actions at Yecheon to a Medal of Honor. Bussey said he wasn’t recommended for the Medal of Honor for racist reasons. He lived for much of his life in Daly City. He pioneered setting up African American businesses in the Hunters Point-Bayview district of San Francisco during the 1960s.

Listen to this podcast “Fighter Pilot of the Tuskegee Airmen”. Lt Col Bussey’s first battle was at home in what you might call the fight for the right to fight. This is his dramatic story, in his own words.

Sources:

Racheal Seymour, granddaughter

Fe Seymour, daughter

AAERG

SFGATE

African American Military History