Chauncey Spencer, Sr.

Chauncey Spencer, Sr.

November 5, 1906 – August 21, 2002

” I’m no paragon of virtue; I’ve lived like other men. But I know what is evil and what is illegal and what is unacceptable for good human relations.”

~ Chauncey Spencer, Sr. May 17, 1993

Chauncey Spencer, Srs efforts helped influence then Senator Harry S. Truman to fight to establish funding for the training of African American Pilots at Tuskegee Institute for the Army Air Corp that brought about the formation of the pilot group that would become the Tuskegee Airmen.

Chauncey Spencer, Sr. was an African-American pilot, and educator. From Lynchburg, Virginia, he was one of three children of Edward Spencer and noted Harlem Renaissance poet Anne Spencer. One of the most respected families in Lynchburg, visitors to the Spencer home included George Washington Carver, Paul Robeson, James Weldon Johnson, Walter White, Clarence Muse, Dean Pickens, Adam Clayton Powell, Langston Hughes, Thurgood Marshall, and W.E.B. Dubois.

At the age of eleven, he fell in love with flying, yet after graduating from college, no aviation school in Virginia would admit him because of his color. A family friend, Oscar De Priest, the first black Congressman since Reconstruction, suggested that Spencer move to his home district in Chicago to take flying lessons. Spencer moved to Chicago in 1934 and joined with a group of African American aviators in organizing the National Airmen Association of America (NAAA). Working for $16-a-week as a kitchen helper he paid $11 an hour for flying lessons.

In May of 1939, the CPT (Civil Pilot Training program) and the Chicago Defender, the local African American newspaper, decided to organize a “Goodwill Flight” to Washington, DC, to lobby for a change in legislation so African Americans could join the US Army Air Corps. Dale White was chosen to be the pilot of the flight and Chauncey Spencer was selected as the navigator. With a CPT-secured rental of a Lincoln PT-K biplane, White and Spencer left Chicago on May 8, 1939, for their 4,828 kilometer (3,000 mile) round-trip.

Dale L. White (center) and Chauncey E. Spencer (second from right) are greeted by National Airmen’s Association President Cornelius R. Coffey (second from left) at Harlem Airport, Chicago. Chicago businessman James Hill (far left) and author and sociologist Horace C. Cayton (far right) also appear.

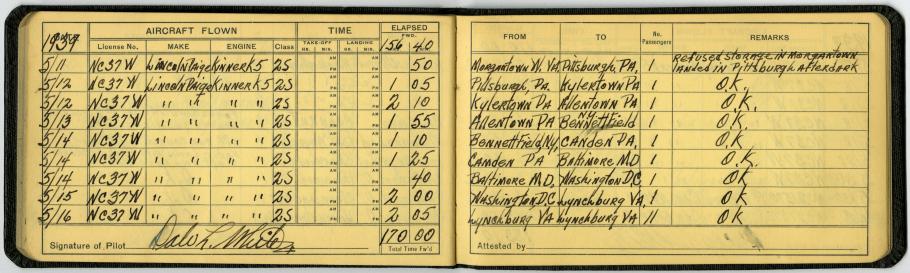

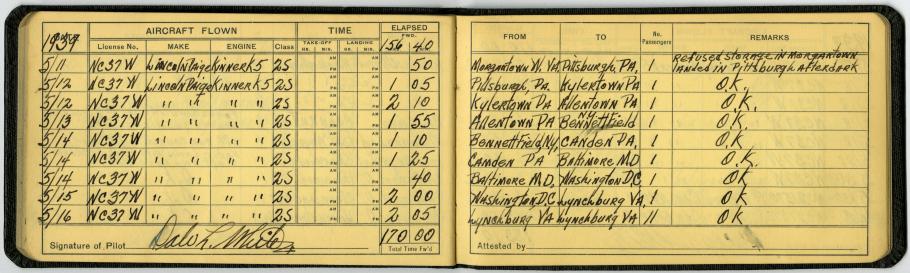

Dale L. White’s pilot logbook provides insight into the flight. May 8 was a difficult day. First, they were “force[d] down in Avilla, Indiana, for six hours due to broken gas lines.” Later that day, White notes that they were “force[d] down with broken crank shaft and nose plate” in Sherwood, Ohio. The Millers, on whose farm they landed, greeted them warmly and the aviators were guests at the local tavern until repairs were complete on May 11.

In the first entry on the second page, White notes in the May 11 “Remarks” section, “Refused storage in Morgantown landed in Pittsburgh after dark.” Without lights on their aircraft, White and Spencer followed a Pennsylvania-Central Airlines transport to the Pittsburgh airport. This was a dangerous move and the two were fortunate that the Civil Aeronautics Authority allowed them to continue the next day.

Though they may have been unknowns to the welcoming Millers in Sherwood or to the people of Morgantown, West Virginia, where they were rejected, White and Spencer’s cause and flight were well known to the African American community in New York. During their stop in the Big Apple, the two attended boxer Joe Louis’s 25th birthday party on May 13 at the Mimo Club.

The next day, White and Spencer landed in Washington, DC. They had scheduled meetings with Senators James Slattery and Everett Dirksen. But perhaps a chance meeting with then-Senator Harry S. Truman had the most lasting impact. Upon meeting them, Truman reportedly commented, “If you guys had the guts to fly this thing to Washington, I’ve got guts enough to see you get what you are asking.” Indeed, Truman did help pass legislation allowing African Americans to participate in the Civilian Pilot Training Program. In 1948, President Truman integrated the armed services by presidential order.

White and Spencer returned to Chicago in a roundabout way. They stopped by Spencer’s hometown of Lynchburg, Virginia. They then made a special pass over Sherwood, Ohio, to salute their new friends, the Millers. And they returned to Chicago as heroes.

Dale L. White, Sr. (left) and Chauncey E. Spencer (right) with Enoch P. Waters, Jr. (editor of the Chicago Defender newspaper) following the completion of their roundtrip flight from Chicago to Washington, D. C., sponsored by the National Airmen’s Association and the Chicago Defender in 1939

Later, while employed by the Army, Spencer worked with Judge William H. Hastie to encourage fair treatment of African American air cadets being trained at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama and other air bases during World War II. He encountered considerable resistance from whites as well as blacks as the Civilian Personnel Employee Relations Officer at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio. Despite this, he persisted and made steady progress towards integration of the Air Force. In 1948, Spencer received the Exceptional Civilian Service Award for service during World War II, the highest honor the Air Force could bestow upon a civilian.

In 1953, the United States Air Force referred to his role in the integration of the military as “unique though strangely unsung.” However, his refusal to drag his feet on integration created resentment among highly-placed officials who wished to see integration fail. Consequently, in 1953 Spencer was charged with disloyalty and accused of being a Communist. He was relieved of his position and his family suffered great humiliation and economic deprivation. In June 1954 the Air Force cleared him of all charges. Spencer and his family would never fully recover from this ordeal. Despite ill-treatment, he continued to maintain his belief in the goodness and strength of mankind and America until his death on August 21, 2002.

Visit the Barron Hilton Pioneers of Flight Gallery to see Chauncey Spencer’s Flight Jacket and Gear.

Sources:

Chauncey Spencer, Jr., Founder, CEO at Chauncey Spencer Education Services, LLC.

ABHM.com

Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum