Dabney N. Montgomery

Dabney N. Montgomery

April 18, 1923 – September 3, 2016

A Tuskegee Airman ground crewman and bodyguard for Martin Luther King, Jr.

Dabney N. Montgomery was born on April 18, 1923 in Selma, Alabama to Lula Anderson Montgomery and Dred Montgomery. He attended the Alabama Lutheran Academy and then Selma University High School, graduating in 1941. After high school, he joined the U.S. Army and was sent for basic training at Keesler Field in Biloxi, Mississippi. After that, Montgomery was sent to Quartermaster Training School at Camp Lee, Virginia (outside of Petersburg), where he received special training in supplies.

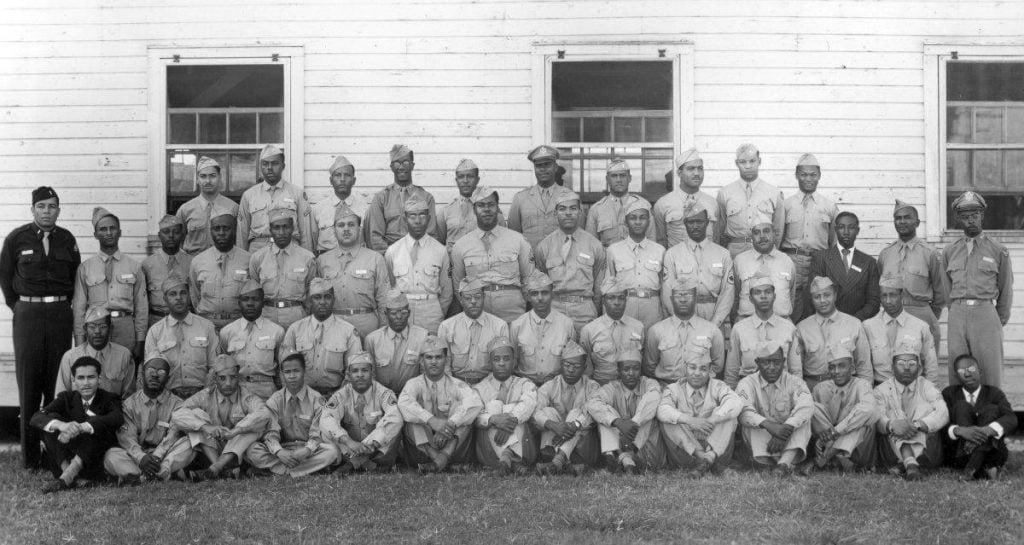

In 1943, Montgomery of the 1051st Quartermaster Company of the 96th Air Service Group, attached to the 332nd Air Fighter Group was deployed to Italy. He served there until the end of World War II.

In an 2015 interview he shared:

“Later that year, three of us were sent to Oscoda, Mich., where we joined the Tuskegee Airmen—the first black pilot corps in the military—as their ground support. When I saw guys who looked like me flying airplanes, I was filled with hope that segregation would soon end.

In late December 1943, the airmen and support units sailed from Norfolk, Va., in 34 ships. We were bound for Southern Italy, which had been liberated by Allied forces just a few months earlier. There were about 15,000 of us.

In early January, we docked in Bari, Italy. The Germans had bombed the area days earlier, so it was unsafe for us to be quartered in tents or houses.

When we disembarked, the sun was setting and 500 of us were transported to an open spot on a mountainside. As we got off the trucks, it started to rain. We couldn’t light a fire for heat and didn’t have shelter, so we slept on the ground as best we could.

The next day we boarded trucks and traveled three hours north to near the airfields. I was in the 1051st Quartermaster Company of the 96th Air Service Group, attached to the 332nd Air Fighter Group. My job was to help set up a supply warehouse.

We began by housing supplies in tents but soon needed more protection from the weather. We found a building in Ramitelli that had been a warehouse, about 6 miles from the airfield.

Everything we did was in support of the Tuskegee Airmen, who flew fighter planes that escorted the B-17 and B-24 bombers over Europe.

One night I had to go to headquarters at the nearby airfield but missed my ride back to the barracks. I had to walk the 6 miles in the dark. On my way, I heard plane engines above that sounded different from ours. When I returned, everyone in my company was out with their guns. The Germans had dropped paratroopers into the area I had just walked through. It was a miracle I made it back alive.”

Montgomery served with the Tuskegee Airmen, the legendary black Army Air Corps unit from 1943 to 1945 in Southern Italy

In 1946, after returning to the United States, Montgomery entered Livingstone College in Salisbury, North Carolina. Montgomery became a member of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity and graduated with his B.A. degree in religious education in 1949. Between 1949 and 1950, he returned to Livingstone College and acquired thirty hours in economic study. He briefly studied economics at the University of Michigan and Wayne State University before going to Boston, Massachusetts, where he enrolled at the Boston Conservatory of Music, studying dance. Montgomery later studied dance with the New York City Metropolitan Opera Dance School before an injury forced him to end his career. In 1955, he began working for the city, first as a Social Service Investigator in the Department of Social Services and later for the Housing Authority. He retired in 1988.

Montgomery was heavily involved in the Civil Rights Movement. For Dabney, the indignities at home stung more because of the noble tasks he performed for his country abroad — serving with the Tuskegee Airmen to help win World War II in a role that would eventually earn him a Congressional Gold Medal.

But at a train station in Atlanta in 1945, carrying an Army duffel bag over his shoulder after receiving his honorable-discharge papers, he was abruptly confronted with Jim Crow America.

“Before I could get in, a white officer threw up his hands [and said]: ‘You can’t come in this door, boy. You got to go around the back,’” Montgomery told Journalist and Aesthetic Realism Associate, Alice Bernstein in a video interview. “‘You can’t come in here; you’re black. You got to go around the corner.’”

In Selma, he tried to register to vote, according to the Bernstein interview. A woman there, he said, told him that he had to find “three white men that would endorse me as a good negro that would not cause any trouble in Selma, Alabama, if I voted.” When he returned with the endorsements, he said, he was denied again. This time, the woman said, it was because he did not own land in Alabama.

But as he left, he noticed a white soldier, fresh out of the Army, just like he was.

“He walked up to the table: ‘I want to vote.’” Montgomery recalled the man saying.

He said the lady replied: “‘Okay, sign your name here. Right here. Okay. You can vote.’”

“That was the welcome that so many of us [blacks] received after fighting World War II,” Montgomery recalled.

The memory stuck. Years later, after he relocated to New York, he saw newscasts of civil rights activists being attacked with fire hoses and tear gas. He decided to return to do his part.

“I’m going and getting a taste of that gas,” he recalled telling his supervisor. “I’m going home and [taking] part in that movement.”

Montgomery served as a bodyguard to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and protected King during the famous 1965 march to Montgomery from Selma, AL. — Montgomery’s home town. Alongside King, he prayed on the steps of the Selma courthouse and, later, walked 50 miles to Montgomery.

Heels from the shoes Montgomery wore in that march hang in the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington.

Sources:

The History Makers

The Wall Street Journal

Washington Post

Wikiepdia