Dorothy Eleanor Olsen (née Kocher

July 10, 1916 – July 23, 2019

Class: W-43-4

Training Location: Houston Municipal Airport (Tex.) and Avenger Field (Sweetwater, Tex.)

Assigned Bases: Long Beach Army Air Base (Calif.)

Planes flown: B-13, PT-19, UC-78

As a WASP, Dorothy Olsen was a civilian pilot, working for the military. Her assignment was ferrying new aircraft of many different types from the factories where they were built to airbases. This freed up male pilots for combat. She died in 2019, at the age of 103.

She was born in Woodburn, Oregon, on July 10, 1916 to Ralph and Frances (Zimmering) Kocher, and grew up on the family’s small farm. She decided she wanted to fly airplanes when she was eight, after reading The Red Knight of Germany, Floyd Gibbons’s biography of World War I flying ace, Baron von Richthofen. Her initial introduction to flight was when she took a biplane ride at a state fair, which inspired her to take flying lessons.

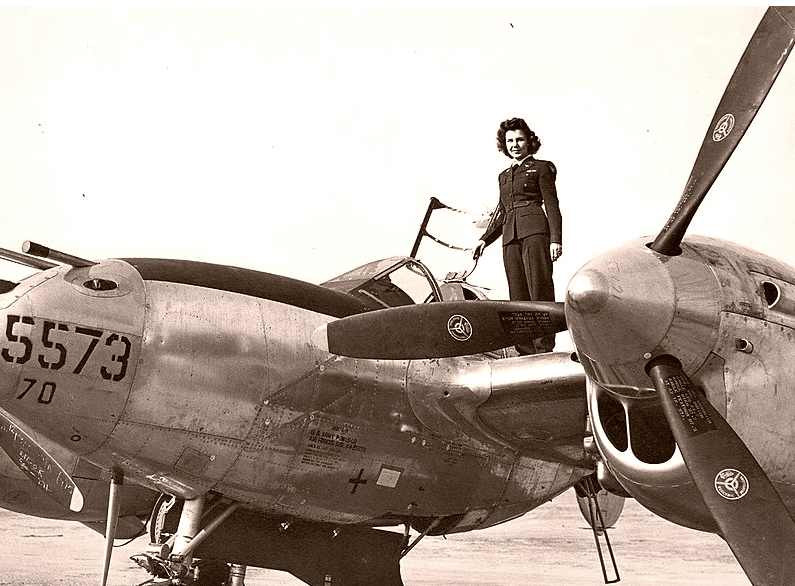

Olsen earned her private pilot’s license as a civilian in the 1930s, taking her checkride in a 40 hp Taylorcraft. Three years later, she was flying twin-engine P-38s, with a total of 3,100 hp.

Prior to joining the WASP, Olsen flew with the Woodburn Flying Club, the Civil Air Patrol in Portland and The Dales and worked as a dance instructor in Portland. She was reportedly one of only three women in the Portland area to have a private pilot’s license

Olsen joined the WASP in 1943 when the program was created. A petite woman, 5 feet tall Olsen embarked on a weight-gaining regimen to make the 100-pound required minimum. There were more than 25,000 applicants, of which 1,879 were accepted and 1,074 graduated.

Olsen was a member of class 43-4 (43-W-4 in some sources), which included 152 students. Her training began in February, 1943, at Houston Municipal Field (now named William P. Hobby Airport) along with half of her class. The other half of the class reported to Avenger Field in Sweetwater, Texas.

She initially hated her training, but stuck with it to avoid the embarrassment of dropping out. She encountered difficulties when her fiancé died and she took time off to attend his funeral, putting her behind the rest of her class. Despite being sick with a cold on her return, she passed a checkride; this avoided her being put back a class, although she continued to struggle to catch up.

She graduated on August 7, 1943. After graduation, her assignment was to the Sixth Ferrying Group in Long Beach, California. She flew 61 missions, and was one of only twelve women certified for night flight.

Olsen would take a pair of good shoes with her on ferry flights, so she could go on dancing dates with men at her destination before having to take off on her next flight. She would leave her name and address in the cockpits of planes she had ferried, to be found later by the combat pilots. Two such pilots wrote her postcards, one reporting that the plane “performed perfectly”, in spite of having been previously flow by a woman.

Once at Cherry Point, N.C., she decided to hold a P-51 on the runway during takeoff, pulling the nose up only when she ran out of airfield.

“I wondered what it would feel like,” she said. “I pushed it hard, and then I pulled the stick back and climbed fast.”

A voice from the tower came over the radio, and she feared it would be a reprimand.

“Come back soon,” the control-tower dispatcher said.

Her daredevil stunts once caused damage to a plane’s front-wheel cowling.

“I suppose I had been hanging upside down at the time,” she said. When she landed, the 7-inch piece of metal fell off on the airfield. The ground crew handed it to her, knowing she would be reprimanded if damage to the plane was found.

She hid the evidence in her footlocker, where it’s been for nearly 55 years, a small reminder of the glory days when anything was possible.

WASP were not, at the time, considered military personnel; she is listed in the Sixth Ferrying Group personnel book with the title of “Civilian Pilot”. When the WASP program ended in 1944, the pilots were discharged at their home base, with no transportation allowance to get back home. WASP were retroactively granted veteran status as part of the GI Bill Improvement Act Of 1977.

According to Olsen, she flew more than 20 different aircraft models, both Army and Navy types. Her favorite type was the P-51. A friend, Debbie Jennings, said she disliked flying bombers because in fighters, “she was by herself and could do whatever she wanted”. Jennings mentioned that Olsen enjoyed scaring farmers on their tractors by flying close to them and at railroad stations also. For her actions, she was reprimanded by her superiors. According to her son, “She felt bombers were like driving buses” and her daughter noted that Olsen felt the P-38 was “an old woman’s plane”.

The extent of her post-war flying is unclear. One source says she flew commercially for Western Skyways. Other sources state she never flew commercially, and not at all after having children. Olsen is reported to have never flown privately after the war; she is quoted as saying, “Why would I want to fly a Cessna when I’ve flown a P-51?”

After the war, she married Harold W. Olsen, and moved to University Place, Washington. The couple had a daughter, Julie (Stranburg), and a son, Kim. Olsen ran antique shops after raising their children. Nerve damage from a dental procedure left her deaf for many years. At the age of 80, she received cochlear implants which restored her hearing.

In 2010, Olsen (along with all other WASP) was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal to commemorate her service. In 2015, she was honored with a flyover of Seattle’s Boeing Field by vintage aircraft for her 99th birthday. In 2016, Olsen celebrated her 100th birthday at Joint Base Lewis-McChord. Also in attendance were fellow WASP Alta Thomas, Betty Dybbro, and Mary Jean Sturdevant.

Olsen died on July 23, 2019, at her home in University Place, Washington, aged 103, and was given military honors at her funeral. Prior to her death, she was one of 38 WASP still alive.

Dorothy Olsen seen with a Lockheed P-38 Lightning during her time as a member of the Women Airforce Service Pilots. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Air Force

Sources:

Texas Women’s University in Denton, Texas

Washington Post

Wikipedia