June 23, 1926 – June 21, 2018

June 23, 1926 – June 21, 2018

Born in Teaneck, NJ, and passed away in Wichita, KS

“We didn’t even know what a Tuskegee Airman was” – George Boyd

It’s true. When you’re in the middle of helping create a story who’s name and legacy will live on, you don’t yet have a name. George Boyd and those who served with him would later find out they were part of a truly significant story…the famed Tuskegee Airmen. Whether in the cockpit, working on an engine, administrating, or any number of roles, these men (and women) of the estimated 15,000 who took part gave us a heroic story of perseverance and accomplish in the face of great odds.

“I wanted to be a military officer is what I really wanted to do,” Boyd told The Journal Times from his home in an interview. “I was in the Army Enlisted Reserve Corps. That ensured that when they called me up, I would report to the Air Corps.”

His first day of active duty was July 20, 1944 — a day burned into his memory. He said he remembered his father dropping him off to catch the bus. It was on his dad’s route to work, he said. “He was going to work, I was going to war,” Boyd said with a soft chuckle.

Boyd was sent to Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, he said, where an isolated Army airfield had been constructed to train black pilots.

These men were segregated and subjected to institutionalized racism: They were not allowed to walk on “whites only” beaches or drink from water fountains used by white men and women.

“There were certain things that you did based on custom and what was safe. What you did was survive,” Boyd said. “We learned survival.

“This was just part of growing up black. We knew we wanted a better way of doing things.”

Military records state that 992 black pilots graduated from Tuskegee Institute, 66 of whom were killed in action, according to military records. But Boyd said he didn’t complete the Tuskegee Airmen training. He said he did go on missions as a radar observer, though.

“We did chase Russian bombers away from the Dew Line in Greenland,” he said.

He served for close to three decades in the U.S. Air Force, first in World War II, then in the Korean and Vietnam wars. He served as an all-weather jet fighter radar intercept officer, squadron commander and combat management engineer, finally retiring as a major in 1970. Dr. Boyd achieved the grade of colonel in the Civil Air Patrol. He was the Commander and Director of the Kansas Wing and Department of Civil Air Patrol. George also served as the Director of Aviation for the State of Kansas, and he worked as an executive in several Kansas Corporations.

(This feature is part of the “Through Airmen’s Eyes” series. These stories focus on individual Airmen, highlighting their Air Force story.)

It was 1944 and the U.S. was in the midst of two battles — a war on two sides of the world and the onslaught of cultural changes on the homefront.

Meanwhile, a young African-American Soldier picked up trash on the white sandy beaches at Keesler Field, Mississippi. He had been briefed that although he was in the service and evidently may fight and die for his country, he could neither walk on this beach unless he was working nor could he swim here because it was for whites only.

Now retired Maj. George Boyd, a 28-year combat veteran and Tuskegee Airman, will never forget the hypocrisy of that order. Boyd, now a resident of Wichita, Kansas, was part of the service during the transition from the Army Air Corps to the Air Force.

Boyd served in World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War. He witnessed the roots of social equality shift within his country and his service; from the integration of the armed forces by President Harry S. Truman in 1948, to the Civil Rights movements of the 1960s.

He recalled the era of segregation; from being refused service at local restaurants to witnessing police brutality in the streets outside the gates of his duty station.

“Most of the time you stayed in the culture that you knew because it was safe,” Boyd explained. “It was easiest to operate within those limitations. You lived in a cultural fear. You were afraid of doing something that would get you harmed even though you aren’t breaking the law.”

Boyd described some of these problems he and many other service members faced, such as not being promoted because they were African-American.

“They gave you a job, and you’d do the job, but instead of giving you the rating they gave everybody else, they’d give you just a (lower) rating,” Boyd said. “Well you’re not going to get promoted if they do that to you, especially if they have everybody else walking on water.”

Despite setbacks, the successes of African-Americans in service, like that exhibited by the Tuskegee Airmen, brought a positive light to the social struggles that inspired a push to utilize everyone’s talents regardless of race.

“The greatest strength of our Airmen is their diversity,” said Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Mark A. Welsh. “Each of them comes from a different background, a different family experience and a different social experience. Each brings a different set of skills and a unique perspective to the team.”

The Air Force developed programs and policies to ensure equality within the service, such as equal opportunity, with the mission of breaking down social or institutional barriers within the workplace.

As the government and the military put in place specific policies to prevent discrimination, society began to adjust and social changes happened gradually throughout the years.

“It’s a whole lot better now because I think they are realizing people’s potential,” Boyd said. “That’s a learning process and it takes some time. Cultural change takes place at your dinner table, in your home. The things you teach your children — that’s culture, that’s where the change takes place.”

Boyd served for nearly three decades as both an enlisted Airman and a commissioned officer fulfilling in a variety of positions, including detachment and squadron commander, combat management engineer and all-weather jet fighter radar intercept officer.

“I went into the service with two years of high school and came out with two Ph.D.s,” said Boyd in regards to education. “The Air Force has a lot of opportunities. I think it’s so important.”

Boyd continues to share his knowledge with the community. He is currently a colonel in the U.S. Civil Air Patrol and recently retired command of the unit in Wichita. He spent many years promoting the importance of education and contributing to the development of youth within the local community.

Fast forward 60 years after he cleaned that segregated beach in Mississippi, Boyd is standing in a luxury hotel near what is now Keesler Air Force Base. He is standing at the window, his gaze set upon a familiar beach.

A young man once forbidden from even walking on this stretch of land because of his skin color, can now freely stroll the sandy beach in peace. He heads down to the water and takes pictures with his wife. A smile crosses his face as he realizes how far the country has progressed.

“This is the best country in the world, because in no other country do changes take place like they take place here,” Boyd said . “I have a view on life that says we can do better, and we are doing better. Try your best, do your best and be the best you can be – aim high.”

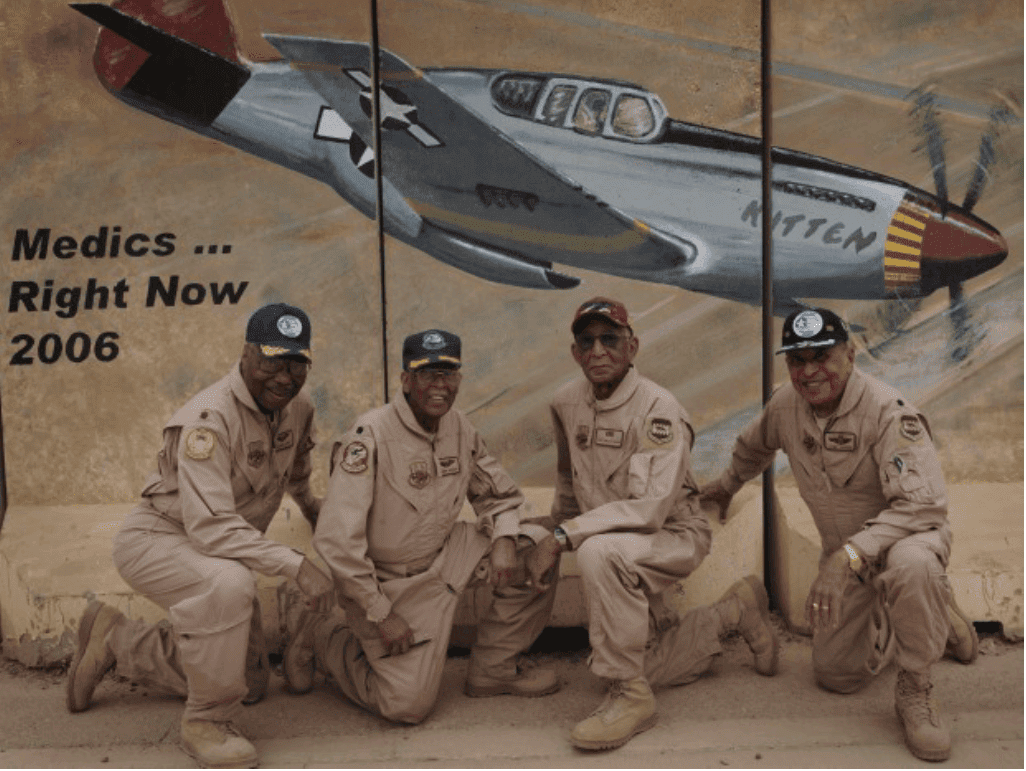

Tuskegee Airmen, retired Major George Boyd (from left), retired Lt. Col. Alexander Jefferson,

former Staff Sgt. Phillip Broome and retired Lt. Col. James Warren, pose April 24 in front of barrier art here showing a “Red Tail” P-51 Mustang.

The famed World War II pioneers met with Airmen assigned to the 332nd AEW. (U.S. Air Force photo/Senior Airman Elizabeth Rissmiller)

Sources:

Civil Air Patrol | Kansas Wing

McConnell to hold service for Tuskegee Airman George Boyd

George Boyd – Patriot Features

Tuskegee Airman reflects on diversity – U.S. Air Force

Patriot Features – Watch the video “Boyd, a service story”

The CAF Red Tail Squadron is a volunteer-driven organization dedicated to educating audiences across the country about the history and legacy of the Tuskegee Airmen, America’s first black military pilots and their support personnel.

Tuskegee Airmen archive images courtesy of Historical Research Agency, Maxwell, AFB, Alabama