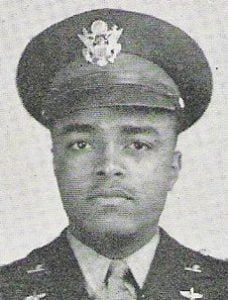

1st Lt George Thomas McCrumby

1st Lt George Thomas McCrumby

October 21, 1917 – February 29, 1944

Class: 43-A-SE

Graduation Date: January 14, 1943

Graduation Rank: 1st Lt

Unit: 79th Fighter Group, 99th Fighter Squadron

Service # O-796265

George was born in 1917 to Benjamin McCrumby and Cary Goodson. He grew up in Fort Worth, Texas. His mother passed in 1938, and his father, two years later. After graduating from high school, he worked as a dining car employee in Fort Worth.

McCrumby graduated from flight training on Jan. 14, 1943, at Tuskegee Army Air Field in Alabama. He deployed to North Africa with the 99th Fighter Squadron in April; the squadron flew its first combat mission on June 2. The 99th Fighter Squadron moved to Italy in July, and remained in that country for the rest of the war.

In late January 1944, 37,000 Allied troops launched an amphibious invasion of Anzio, Italy, about 35 miles south of Rome. Although they established a beachhead by nightfall, they could not break out of the city. On Jan. 23, Luftwaffe aircraft attacked the Allied positions and two hospital ships in the harbor. Eight fighter squadrons, including the 99th, took on the task of repelling enemy air raids.

On Jan. 27, McCrumby and 15 other pilots from the 99th Fighter Squadron spotted a group of German fighters attacking Allied ships. The 99th attacked: When the smoke cleared, 10 enemy planes had been destroyed. McCrumby’s plane was damaged as he chased an enemy plane, but he was able to return to the squadron’s base without incident.

That would not be the case nine days later.

On Feb. 5, 2nd Lt. McCrumby and Capt. Clarence C. Jamison battled with six German planes.

“Something hit underneath the ship,” McCrumby told a reporter from The Afro-American, a Baltimore newspaper, a few days later from his hospital cot. “Then another burst cracked the side of my cockpit, plunging the plane into a dive at 4,000 feet. I tried to pull out but had no control. The elevators had been knocked out. I had no alternative but to jump.

“I tried the left side, but the slipstream knocked me back. Then I tried the right side and got halfway out, when again the slipstream threw me against the fuselage. I struggled until all but my right foot was free and dangled from the diving plane until the wind turned the ship at about 1,000 feet and shook me loose. I reached for the rip cord six times before finding it, but my parachute opened immediately, landing me safely in a cow pasture.”

British soldiers from a nearby anti-aircraft unit took McCrumby to the Anzio Beach Field Dispensary in Italy. McCrumby spent four days in an evacuation hospital before he was transferred to a general hospital for scratches on his face and right leg, and a sprained ankle.

“I couldn’t believe it was my time to die, but several times it looked like my finish as the ship lost altitude fast before I was untangled,” McCrumby said. “It was diving at 350 miles per hour. There I was, hanging like a broken tree limb.”

When McCrumby was told he would receive a Purple Heart, he said: “All I want is to get back into the air.”

McCrumby returned to the air, but his last flight was Feb. 29.

“About 10 or 15 minutes after take-off, just southwest of Gaeta Point (in central Italy), and about 3 miles out to sea, Lt. McCrumby dropped down below the formation slightly, and made a 180-degree turn, and headed back for our base,” 1st Lt. Howard L. Baugh wrote in a

military report. “No one in the formation received any radio message from him, and since we were still in our own territory, no one turned back to return with him. He or his airplane has not been seen or heard from since.”

McCrumby’s official date of death is listed as July 15, 1945. His name is engraved on the Tablets of the Missing at Sicily-Rome American Cemetery. His remains have never been recovered.

According to a government database, McCrumby was awarded a Purple Heart with one oak leaf cluster for his military service.

Sources:

Findagrave.com

HonorStates.org

WikiTree.com

Saint Louis Daily Dispatch