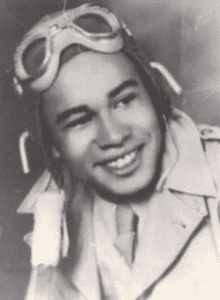

Major George W. Biggs

Major George W. Biggs

July 2, 1925 – Sept. 19, 2020

Unit: 477th Bombardment Group

Born George Washington Biggs in Nogales, Arizona, on July 2, 1925, he was the son of Dolores and Levi Biggs. He grew up in a family with a strong tradition of military service. George’s father, Levi, was a proud member of the 25th Infantry Buffalo Soldiers. In 1918, during World War I, he spent time at Camp Little in Nogales. Levi Biggs remained in the Army for 26 years, and eventually rose to the rank of a Master Sergeant. He and Dolores had five children. George was the oldest.

Biggs registered for the draft on July 3, 1943, the day after his 18th birthday. To contribute to the American war effort, he did not want to be assigned to jobs like being a cook, which were one of the few options available for African Americans who wanted to serve. Three months later, he enlisted in the Army. Once he made it through Basic Training, he qualified for Aviation Cadet Training at the recently activated Keesler Field in Biloxi, Mississippi. From there, as one of those who trained at Tuskegee Army Air Field in Alabama for combat in Europe, Biggs became part of history. What is remarkable is that when George joined the military, he did not yet know how to drive a car, much less have any experience with aircraft!

He trained at the Tuskegee Army Air Field in Alabama during World War II as a part of a bomber crew and finished his enlistment as a Master Sergeant in 1946. The group trained on Boeing-Stearman PT–17 Kaydets and Fairchild PT–19 Cornells, and learned to fly Curtiss P–40 Warhawks, Bell P–39 Airacobras, Republic P–47 Thunderbolts, and North American P–51 Mustangs painted with distinctive red tails.

He underwent a program in aerial gunnery at Tyndall Army Airfield, near Panama City, Florida. At Godman Army Airfield at Fort Knox, Kentucky, he was selected for navigator/bombardier training in September 1944. This would prepare him for missions in Europe on the B-25 Mitchell. In April 1945, shortly before Nazi Germany capitulated, Biggs completed navigator training. Two months later he became a Master Sergeant in the US Army Air Forces. Then, he moved to the final hurdle: bombardier training. When that was finished in October 1945, the war had been over a month. Missing combat really frustrated Biggs.

After the war ended, Biggs re-enlisted as a non-commissioned officer in the newly created U.S. Air Force and “started all over again,” recalled his daughter Rose Biggs-Dickerson. “It took another four years before he was recommissioned as an officer.” During the Korean War he flew bomber missions from Okinawa, Japan, on Boeing B–29 Superfortresses and from South Korea on Martin B–26 Marauders.

When the Korean conflict ended, he was stationed at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base near Tucson, Arizona, and also flew Boeing B–47 Stratojets. Biggs-Dickerson said her father was one of the first African American officers stationed there and he “worked hard to help other Black airmen settle into life at the base.”

Biggs later flew Boeing B–52 Stratofortress bombers during the Vietnam War and earned numerous military honors. Despite his accomplishments, he spoke often of the discrimination he faced in the military.

At the end of the Korean War, Biggs was stationed at Little Rock Air Force Base and then at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Tucson.

He was a navigator at Davis-Monthan assigned to one of the three squadrons of B-47 bombers of the Strategic Air Command. He was also among the first African American officers at the base.

“There were lots of obstacles he overcame. He was a navigator at the time the base was integrating, and he said the Anglo pilots did not accept him,” his daughter Rosario Biggs-Dickerson said. “They were still cautious of him. He mapped where they were flying.”

The story goes that the pilots were in a territory they weren’t supposed to be: disregarding Biggs’ instructions.

“When they finally figured out that he was helping them, he did get them out of enemy territory,” Rosario said. “They apologized to him for how they treated him. But, yes, there were a lot of challenges for him at this base, and at other bases, too.”

Despite his own obstacles, during his time at Davis-Monthan, Biggs educated, mentored and helped airmen overcome various challenges they faced. Biggs rose to the rank of major and served in his third war, Vietnam, and flew missions on the B-52.

In July 1970, he retired from the Air Force. He moved back to Nogales and served as an agent for the U.S. Customs Service.

Biggs lived to see public recognition for the accomplishments of the Tuskegee Airmen. Receiving a bronze replica of the Congressional Gold Medal in 2007 and getting a salute from President George W. Bush meant so much to him. Six years later, Arizona Governor Jan Brewer signed a law establishing the fourth Thursday in March as a day of commemoration for the Airmen.

George W. Biggs displays his copy of the Congressional Gold Medal at the Pimeria Alta Historical Society buillding in Noglas in 2007.

Indeed, George Washington Biggs devoted most of his adult life to causes greater than himself. He left behind much good will and respect. Biggs is survived by his wife, Olga, 10 children, 22 grandchildren, and 24 great-grandchildren.

Visit the Red Tail Virtual Museum to learn about Davis-Monthan Air Force Base renaming center after Major Biggs.

Sources:

AOPA.org

NationalWW2Museum.org

Nogales International