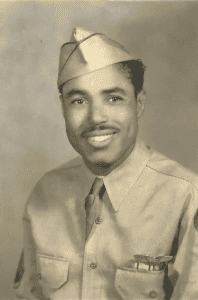

Harold J. Beaulieu

Unit: 617th and 619th Bomb Squadrons of the 477th Composite Group as a Photography Laboratory Technician (945).

Beaulieu ran the photography lab at Freeman Field. His first years of service in the U.S. Army were spent in the all-Black infantry unit at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, in a group known as the Buffalo Soldiers, a nickname carried over from the years after the Civil War. There, he learned aerial photography.

In 1942, he earned his wings and became a Tuskegee Airman.

After the Black officers at Freeman Field refused to sign the order and were arrested, Beaulieu was concerned the Army would not want pictures of the event made public. In secret, he rigged a shoe box to hide his camera. As the men were being arrested, he snapped pictures covertly. He succeeded. He mailed the photo to the Pittsburgh Courier, a leading African-American newspaper.

On April 28, a single photograph, the only known image of the Tuskegee Airmen’s arrest, was published on the front page.

Beaulieu’s grandson Bryan Avery remembers how his grandfather treated photographs with deep reverence, as if they were “a memory that never fades away,” he said.

He had heard his grandfather’s stories about the time he fashioned a camera out of a shoe box and took secret pictures. But Avery never understood the critical role his grandfather played until the junior year of his high school when his family was invited to a local reunion of the Tuskegee Airmen. James Warren, now a colonel, and the other officers, retold the story.

“I always tell people this photograph is sort of one of the first viral photos,” Avery told IndyStar. “Pictures like my grandfather’s, pictures of George Floyd, pictures of what’s going on in Ukraine right now: without those pictures? People don’t know there’s something to stand up for. I think that that’s so important.”

With the photograph of the arrest splashed across the nation’s newspapers, it became difficult to deny what had happened, Avery said. The arrested officers also passed messages to the outside world, the NAACP, and the press, from within the confines of Godman Field, Kentucky, where they were being held.

More than 50,000 telegrams and letters from citizens protesting the arrest of the officers were sent to the War Department, Congress, and President Franklin Roosevelt. Roosevelt died days later on April 12 and was replaced by then-Vice President Harry Truman, who soon took notice of the arrests at Freeman Field.

On April 23, 1945, the 101 arrested officers were released under the orders of the U.S. Army Chief of Staff, Gen. George Marshall, ordered they be released immediately.

Although none of the men received prison terms, they hardly left unscathed: all were issued formal letters of reprimand to their permanent military records, which was considered in any future promotion to higher rank.

A lone officer was convicted for the events. Lt. Roger Terry, who had been charged with “jostling” a white officer, was found guilty of “offering violence against a superior officer,” slapped with a $150 fine, and promised he would never see promotion.

War historians today point to the Freeman Field mutiny as a major catalyst for the eventual desegregation of the U.S. Army in 1948, with President Harry Truman’s executive order.

“The military men known as the Tuskegee Airmen deserve credit not only for serving their country with distinction in battle, but also for entering the civil rights arena and paving the way for later desegregation efforts,” Higginbotham wrote in the 2016 paper. “The price these men paid for their patriotism was high; consequently, the debt owed to them is immense.”

It would be 50 years before the 104 Black officers arrested at Freeman Field — 101 for refusing to sign the order, and the three for “jostling” the white officer — would be absolved. At the Tuskegee Airmen annual banquet in 1995, the Air Force Chief of Staff Ronald Rogleman announced the military had, at last, expunged the letters of reprimand from the permanent records of the airmen.

Beaulieu, who changed the world with his photograph, died of cancer at age 83 in 1991. His grandson said it was caused by exposure to Agent Orange, a chemical defoliant used by the U.S. military in the Vietnam War, where he served.

Last April, Avery carried on his grandfather’s legacy by publishing a children’s book “The Freeman Field Photography” that told what happened at Freeman Field in April 1945 from the point of view of the fictional daughter of one of the arrested officers.

Reflecting on the legacy of his grandfather and Freeman Field, he said, “The oppression we fight changes from time to time, but we still need to work towards that freedom.”

Hear the full interview: ‘The Freeman Field Photograph’ author, Bryan Patrick Avery on his Tuskegee Airman grandfather, Sgt. Harold J. Beaulieu, 3/21/2022.

Learn more about the Freeman Field Mutiny

Sources:

Indystar.com

Craig Huntly, Tuskegee Airmen Subject Matter Expert

Bryan Patrick Avery, grandson of Tuskegee Airman grandfather, Sgt. Harold J. Beaulieu

These images taken by Sgt. Harold J. Beaulieu, shows the 101 Black men from the 477th Bombardment Group arrested in the ‘mutiny’ at Freeman Field’ in 1945. Here they are about to board aboard six Douglas C-47 Skytrains to Godman Field, Kentucky. Beaulieu took the only photograph to survive the Mutiny at Freeman Field. Other photographers reportedly had their cameras confiscated, broken, or film destroyed. Beaulieu captured the scene of the arrest with a camera hidden in a shoebox and a shutter release cord. The photo appeared in the Pittsburgh Courier. The incident was a catalyst for the desegregation of the US armed forces.