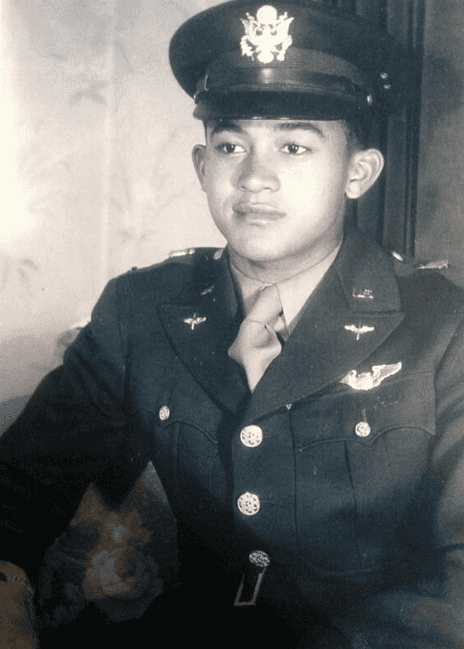

Class 44-D-TE 4/15/1944 2nd Lt. 0828041 Georgetown, IL

Class 44-D-TE 4/15/1944 2nd Lt. 0828041 Georgetown, IL

April 13, 1921 – August 16, 2013

Unit: 617th Squadron, 477th Bombardment Group Medium

“We had to fight for the right to fight for our country.”

Alexander was born April 13, 1921, in Georgetown, Ill., the son of a coal miner.

The family was so poor that Alexander, the second of nine children, walked to school barefoot.

His family couldn’t afford shoes.

But by 1944, as an Army lieutenant, it wasn’t shoes that mattered — but wings.

“My first true feeling of freedom came flying that airplane,’’ Alexander told the News & Record in a 2001 interview. “All that power seemed to be just surging through me. There wasn’t any discrimination up there.’’

Before 1940, blacks were not permitted to fly in the U.S. military. And though they have participated in every American war, Alexander, 86, said they never were welcome.

“This was a white man’s war, we don’t need any Negroes,” he said, recalling a statement President Wilson made during World War I.

Alexander said the Tuskegee Airmen performed better than their white counterparts because they had more training.

“When we weren’t wanted, we just continued training,” he said.

Most of the Tuskegee Airmen also had either a college education or previous flying experience, compared to white pilots who could join the Air Corps after high school.

Alexander started to feel the effects of racism while in high school in Georgetown, Ill.

After his principal privately inducted him into the National Honor Society, the school hosted a public induction ceremony for 30 white students. And though he was first in his class, the school downgraded him to salutatorian. Teachers told him he didn’t need to go to college.

Alexander said he was “pointedly and publicly ridiculed” while attending the College of Commerce at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. One professor gave him low scores on papers, accusing him of plagiarism. Another told him he should be the person to “sweep the factory floors.” He transferred to the University of Michigan and planned to complete his degree and then enroll in the Army Air Corps.

On Sept. 16, 1942, he watched a movie about Marines that had him excited enough to think he was ready to join even sooner.

Then the draft notice came.

“All the patriotic vibes that were running through my body came to a halt,” he said. “I knew I wasn’t wanted.” Though President Roosevelt had mandated the inclusion of blacks in the military, Alexander knew he would never see combat. He served in the infantry for five months and earned the rank of corporal before he was transferred to the Air Corps.

After more than 100 Tuskegee Airmen were arrested for attempting to enter a whites-only officers club, all black airmen were interviewed.

“I think we all told them the same thing,” Alexander said. “I want to be treated like any other officer in the military, and I want to go to combat.” Alexander flew a B-25 bomber, but that type of plane was never flown in combat by a black pilot.

Even the black pilots who were sent to combat did not receive the same treatment as white servicemen, he said. “The Tuskegee Airmen were held in Berlin until all the ticker-tape parades were over,” he said.

Theodore Brooks, former president of the Heart of Carolina Chapter of Tuskegee Airmen, a nonprofit that honors the history of the airmen, said the pilots had a second battle to win after the defeat of the Germans: racism.

“Instead of being greeted as heroes, they were relegated to the same second-class citizenship they left,” he said.

Alexander was discharged from service in 1945 and went on to get a bachelor’s degree from the University of Illinois in 1947 and a master’s degree in accounting from Duquesne University in 1950.

He taught accounting at several universities, including N.C. A&T, where he started the accounting major program. After working at other schools and owning a vending business, Alexander retired in 1986 and came to Greensboro to build his own home.

Along with the other Tuskegee Airmen, Alexander received a bronze Congressional Gold Medal replica on March 29, 2007.

As for the future, Alexander hopes that “race becomes a nonissue, that we are accepted on our own merit.”

We salute Mr. Alexander, who passed on to Blue Skies in 2013.

Tuskegee Airman Harvey Alexander, far right, with his flight crew

Sources:

The CAF Red Tail Squadron is a volunteer-driven organization dedicated to educating audiences across the country about the history and legacy of the Tuskegee Airmen, America’s first black military pilots and their support personnel.