Helen Richey

Helen Richey

November 21, 1909 – January 7, 1947

Class: 43-W-5

Training Location: Avenger Field (Sweetwater, Tex.)

Planes flown: PT-19, BT-15, B-25, C-47

Assigned bases:

New Castle Army Air Base (Wilmington, Del.) and Fairfax Army Air Field (Kansas City, Kan.)

Helen Richey was an aviation pioneer known for being the first woman to be hired as a pilot for a commercial airline on a regular scheduled run in the United States. Helen was also the first woman to pilot airmail and one of the first female flight instructors.

Helen was born in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, in 1909. She was the youngest daughter of the five children of Joseph Burdette Richey and Amy Winter Richey. Her father was the superintendent of the county schools from 1902 to 1935. Helen grew up outdoors, playing with her brothers and watching planes from the national post office. She graduated from high school at McKeesport High School in 1927.

Her first plane ride was sitting on the bags of letters on a courier flight between McKeesport and Cleveland. After following the routine of the aircraft and meeting famous pilots, such as Ruth Elder, Helen decided that she also wanted to fly.

Her first airplane ride was sitting on mail sacks on a 130- mile airmail flight from McKeesport to Cleveland, Ohio’s Airport. After seeing famous pilots on the flight, including Ruth Elder, she decided that she wanted to fly. In her biography, Propeller Annie, by Glenn Kerfoot, he states that she told a friend, “I’m going to fly…I’m going to be good enough to earn money at it, too. It’s what I want to do with my life.” For a time, her father objected, but with the support of her mother and Helen’s insistence, he eventually relented.

In April of 1930, Richey enrolled as a student pilot at Bettis Field’s Curtiss-Wright flying school and on June 28, 1930, she earned her pilot’s license. In December 1930, Richey was granted a limited commercial pilot’s license by the Department of Commerce. During the 1930s, Richey set a number of records and placed in several races, including as a co-pilot to Amelia Earhart in the 1936 Bendix Race.

Although her plane was not designed for risky stunts, Helen tried loops and acrobatic flights, while gaining experience to qualify as a commercial pilot, with the aim of flying on passenger lines. In December 1930, she obtained her commercial pilot license. On August 6, 1931, her father presented her with a small plane for four people. In the following years, Helen participated in various air shows, exhibitions and races in various states. Some of these competitions were for women only.

Endurance Flight

In December 1933, Richey participated in an endurance flight with Frances Harrell Marsalis. Their plane dubbed, “Outdoor Girl,” for the cosmetics company sponsoring the flight, took off from Miami on December 20, 1933. For ten days, the plane circled and bounced over that city with the women taking turns at the controls. Pilots Jack Loesing and Fred Fetterman provided the 83 refueling flights plus other airdrops including food, water, repair materials, suntan lotion, and rubbing alcohol for tired aching muscles.

Refueling was strenuous and potentially hazardous. To refuel, a pilot had to climb out of the overhead hatch, grab the nozzle dangling in the wind, and shove it into the opening of the gas tank. Marsalis likened this process to “…wrestling with a cobra in a hurricane….” If the nozzle became detached from the tank, the person handling the task might be sprayed with gasoline. Oiling the engine and replacing used oil often had the same result. On a refueling on the sixth day of the flight, the nozzle came loose and tore a hole in the fabric of a wing. Richey climbed out on the wing and repaired the hole with needle and thread.

After surpassing the previous endurance record, Marsalis made a perfect landing to end the flight on December 29, 1933. Officials verified that they had set a refueling endurance record staying aloft 237 hours and 42 minutes flying 23,700 miles, almost the distance around the world at the equator, consuming eight tons of gasoline.

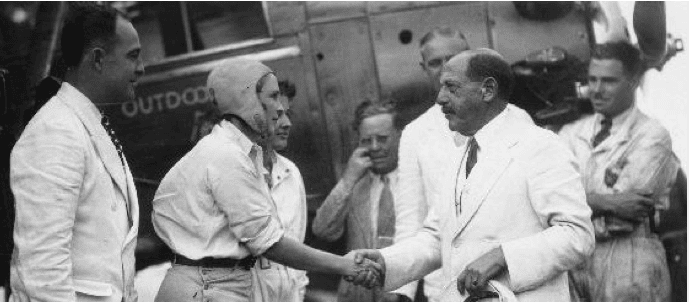

Frances Marsalis and Richey after their endurance flight in a Curtiss Thrush, sponsored by “Outdoor Girl” cosmetics

In 1934, she won the National Air Meet for Women in Dayton, Ohio. In the same year, Capital Airlines, from Greensburg, a company that would later become United Airlines, hired Helen as a pilot. Its first scheduled flight was made on December 31 between Washington, DC and Detroit. The company justified its hiring to the Department of Commerce eight months later when asked that its flights were very successful among passengers and believed that it would lose sales and audience with its departure. The department then recommended that she fly only three times a month and also that she should not fly in bad weather. The pilots’ union prevented her membership because she was a woman and frustrated with the reduction in her flights, Helen resigned in August 1935. The Bureau of Air Commerce then offered Helen a new job as an air marking pilot for the government. She stayed with the air marking service until 1937 when the job was completed. In 1940 Richey was the first woman to earn an instructor’s license and she was appointed an instructor for air cadets at Pittsburgh – Butler Airport. In 1942, she joined the American wing of the British Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA), where she ferried aircraft and needed materials throughout the British Isles. Richey headed the ATA’s American Group from 1942 until April 1943.

Second World War

Helen received a letter from her friend Jacqueline Cochran in January 1942, inviting her to apply for the female division of the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA) of the United Kingdom. Anxious to participate in the war effort, Helene signed up, was accepted and presented herself to the division in Montreal. After three weeks of conducting flight tests and medical examinations, she traveled to England on a train in March of the same year. Assigned to White-Waltham airfield in Maidenhead, Berkshire, she flies for thirty hours on Magister and Tiger Moth planes. It took about 90 hours of flight to the end of June 1942 on several aircraft. Asking ATA pilots to fly on different aircraft was not uncommon on missions. There were instructions in the booths on how to handle each one.

In September, Jacqueline said that she was returning to the United States at the request of General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, to organize a group of female pilots. Helen was responsible for the team of twenty women aviators who were working for ATA in the UK at the time. Meanwhile, Helen began to give in to the pressure of being the team leader and also a pilot and with news that her mother had become seriously ill, Helen resigned from the ATA and flew back home in March 1943.

WASP

When Helen returned home, she started to get impatient. She missed her planes and missed the war effort. So, she signed up for Women Airforce Service Pilots, a service for female pilots that her friend Jacqueline Cochran returned to the United States to organize. In September 1942 the WASP was already making several flights in the service of the Army. Having flown about two thousand hours in her career, Helen was quickly accepted and started training in Sweetwater, Texas, in July 1943. Assigned to Newcastle County Airport in Delaware, she flew about ten different missions.

In March 1944, she was transferred to the Fairfax base in Kansas City, where she trained with bombers and cargo planes. In September she returned to Newcastle, where she stayed until the WASP was disbanded. In the 20 months working for the group, Helen accumulated 300 flight hours on 27 different aircraft.

Last years

Helen came home. The few places for pilots were reserved for the men who returned from the war. Her life ended up entering a period of lack of prospects, where Helen did not know what to do. Tired, she decided to move to New York City. Although she received visits and encouragement from WASP colleagues, Helen did not seem interested, preferring to stay locked up in her apartment, reading. She became more and more depressed. Her sister, Lucille, upon visiting her, noticed that she seemed unusually quiet and depressed, somewhat disconnected from reality.

Death

Helen died in her apartment in the city of New York, on 7 of January of 1947, after 38 years due to a drug overdose. Her death was recorded as suicide. She was buried at McKeesport and Versailles Cemetery in her hometown.

Legacy

In recognition of their service to the country and the war, Helen and other WASP women were posthumously awarded the United States Congress Gold Medal in March 2010.

Visit the WASP Virtual Museum to see the Helen Richey marker in McKeesport, PA

Sources:

Air and Space Museum

Explore PA History

San Diego Air and Space

Texas Women’s University, Denton, Texas. WASP collection

WWII Women Pilots