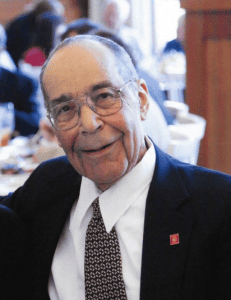

Jack David Bryant

Jack David Bryant

June 5, 1927 – December 20, 2016

Growing up in Dowagiac, Michigan, Jack Bryant knew he wanted to be a pilot. According to Jack, every kid growing up in the 1930s “just wanted to fly.” He collected model airplanes, which he hung all over his bedroom.

But unlike every kid who has a dream, Jack is someone who got to live it. In 1945, at the age of 18, Jack entered the Army Air Corps and began training to become a Tuskegee airman.

Joining the military the same month he graduated high school was scary and intimidating, but Jack had someone leading the way — his older brother, Joseph, a B-25 bomber pilot. Joseph, who was two years his senior, helped Jack prepare to face the challenges of the rigorous training program at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, the training center for all black fighter pilots during World War II.

It was the only option for young African-American men who wanted to serve their country at the time. As Jack, 85, explained, when segregation of blacks and whites was in full force, the only positions available to blacks in the military were in food service or hospitality.

“At that time, the only categories that an African-American could serve in the Navy were as a cook or a steward; in the Army, he could only be in the quartermaster’s corp. There were no officers,” said Jack.

Joseph heard about the flight training program in Tuskegee, Alabama, enlisted, and eventually “got his wings.” Jack joined him two and a half years later.

“I became of age and I wanted to follow in my brother’s footsteps… I asked him for help to get into the program, and he helped me immensely,” Jack said, which was no small feat. “You had to take a pilot’s test — many of the draft boards would not give you the pilot’s test. Some people went to 12 different draft boards to volunteer to serve their country, and they wouldn’t give them the test… I had to travel over 100 miles to go take my test. That’s crazy. Anyway,” he said, cracking a smile, “I passed the test.”

Tuskegee experiment

Jack explained how the pilot training program was referred to as the Tuskegee “experiment” at the time, as the common perception in the military was that African-Americans were unfit for combat.

“The federal government commissioned a report to study the African-American, and the report got back to Congress saying that the African-American didn’t have the mentality or the courage to operate complex machinery or to fight. Through the efforts of the black community, the NAACP, Eleanor Roosevelt and a whole host of others, they lobbied the president to start a program to train African-American pilots.

“The program was designed to fail,” Jack continued. “Getting into the program wasn’t easy, and staying in the program was not easy, either.”

However, the program went on to be a rousing success, sending 450 of the original 996 trained pilots into action overseas. While 150 lost their lives in accidents or combat, the famous 332nd fighter group, known as the “Red Tails” for their aircraft paint scheme, lost very few bomber they escorted.

The Tuskegee airmen’s commander, Colonel Benjamin Davis, was the first black Air Force General but was given the “silent treatment” by fellow officers for four years, said Jack.

There is something else that many don’t know about the Tuskegee airmen, the veteran added. “Everybody associates it with the Red Tails, which are fighter planes. But the Tuskegee airmen also flew bombers. A B-25 is what my brother flew, and that was my goal.”

The war was over before Jack ever saw combat; he was still in pre-flight training when WWII officially ended in September 1945. Jack was discharged in 1946.

He returned to his home state of Michigan and earned his degree in engineering at the University of Michigan, followed by a master’s from Northeastern. He started his Boston-based engineering firm, Bryant Associates, in 1976.

He and his wife, Vernita, moved to Cohasset in 1986. They have two children: son Jeffrey, who followed his father’s footsteps to become CEO of Bryant Associates, and daughter Saadia, who is director of brand development for Crabtree and Evelyn.

In 2000, Mr. Bryant was awarded the Freeman Award from the Providence Engineering Society, in 2007 the Congressional Medal of Honor as a member of the Tuskegee Airman and in 2012, the President’s Award from the Greater New England Minority Supplier Development Council. In his spare time, he enjoyed listening to music, gardening, building model trains at the South Shore Model Railway Club and telling stories.

Sources:

ACEC

Findagrave.com

Legacy.com

WickedLocal.com