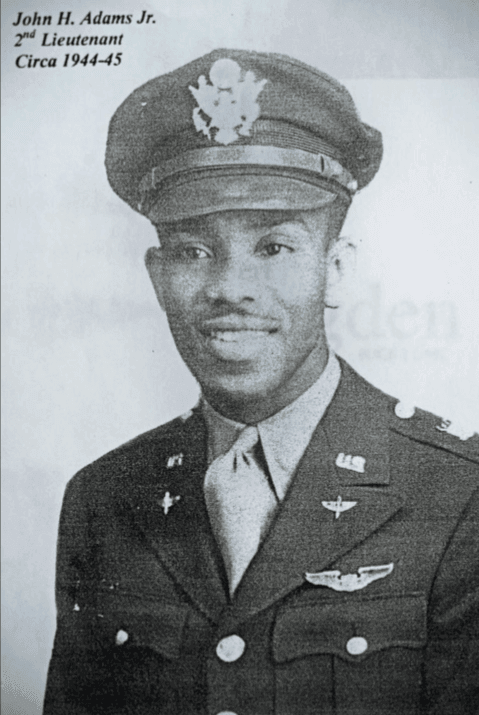

Class 45-B-SE 4/15/1945 2nd Lt. 0842588 Kansas City, KS

Class 45-B-SE 4/15/1945 2nd Lt. 0842588 Kansas City, KS

1920 – DOD

Unit: 332nd Fighter Group

In 2016 John Adams Jr., then 97 years old, still remembered nearly every detail of his training during World War II as a Tuskegee Airman, the first U.S. military unit to allow African-American pilots to fly airplanes in combat.

“I had never been up in a plane before,” said Adams, a member of Kansas City, KS Branch 499, recalling his first day as a student pilot in a PT-17 training biplane. “But my dad used to take me to the airport to watch the planes go up and down, so this was a dream come true. As a youngster, I always liked the idea of flying.”

Drafted into the Army in October 1942, Adams reported to nearby Fort Leavenworth, KS, and then was sent to a school in Boston to learn topographic drafting and engineering. There were five other black soldiers studying with him. Though they took classes with white soldiers, Adams and the other black soldiers were housed separately. Racial segregation was still a part of the military as it was in much of the country, with roles for African-Americans severely restricted.

A broken left leg kept Adams from going overseas with his company of engineers, and after his leg healed, he became a company clerk. As a clerk, one day he noticed a memo that crossed his desk calling for African-American candidates to fly in the Army’s new aviation unit for black pilots. Adams passed the rigorous physical and academic tests and was shipped off to flight training in Tuskegee, AL, in late 1943.

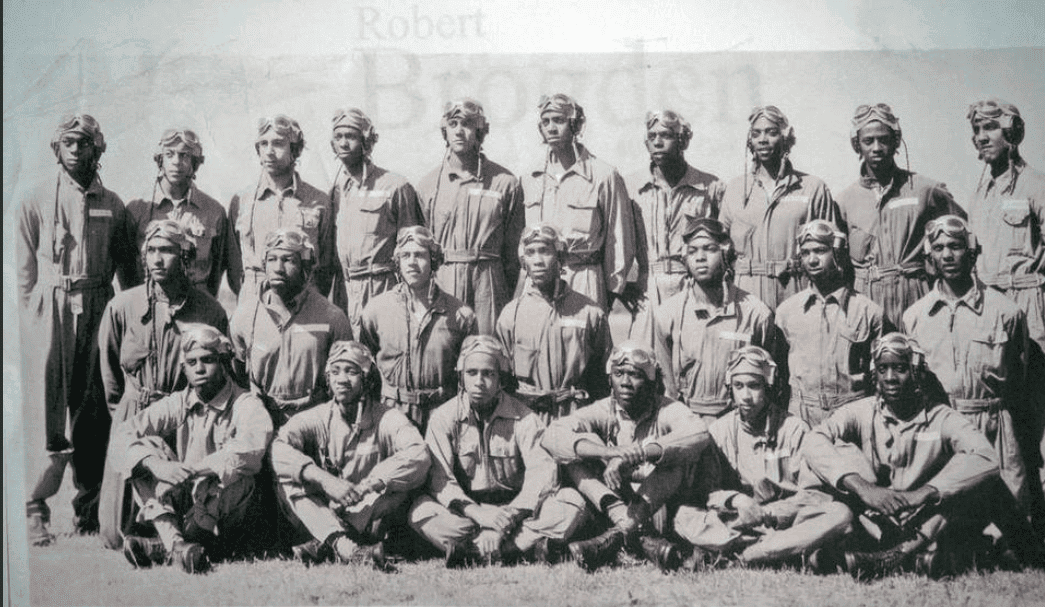

He was joining a military unit that made history by confronting the racial attitudes of the day – that black men would not make good military pilots. In fact, they also had little civilian flying experience – there were only 124 known African- American pilots in the country at the time.

The Tuskegee Airmen, as they came to be known, were the first black pilots in the U.S. military, and they proved their worth. “At that time, blacks were not considered intellectual enough to do many things,” Adams said. “We deserved that chance.”

Civil rights leaders had been pushing for the right of black men in the military to fly since World War I, when they were rejected as pilots. In one famous case, pilot Eugene Bullard, an African-American man who had enlisted with the French air service and already had fought in the skies over Europe in World War I, and applied to serve as a pilot for the U.S. Army when America entered the war in 1917. Despite having proven himself in combat, Bullard was rejected because of his race.

The cause of the Tuskegee Airmen was boosted by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt when, in March of 1941, a few months after the training program began, she took a flight with an African- American instructor for the Tuskegee unit at the controls. The flight was just a half-hour long, but it generated positive publicity and reinforced the notion that black men could be capable pilots. Adams still remembers clearly each plane he flew in training. After learning basic flight in the PT-17 biplane, he and his fellow trainees, about 50, moved on to a more advanced BT-13 Valiant trainer for 90 days, and then it was their turn to fly solo in an AT-6 Texan.

“We did maneuvers, simulated combat, formation flying, all that sort of thing,” Adams recalled. The pilots had to learn how to fly and navigate at night and how to fly using only their planes’ instruments when visibility was bad. They even practiced shooting at towed targets. Adams completed his training in early 1945 and was commissioned as a second lieutenant. He was ready to fly a P-51 Mustang with his unit’s famous red insignia painted on the tail, a marking that led to the nickname “Red Tails” for the Tuskegee fighter and bomber units.

As Adams waited to gather with other pilots at Walterboro Army Airfield in South Carolina and then head to Europe to fight, the news came that they wouldn’t go into combat.

“The Army let us know the war was over and there was no need to go overseas anymore,” he said. He had graduated from Tuskegee just weeks before Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945. Though Adams never got the chance to use his flying skills in combat, he still was part of history. He and 991 of his fellow Tuskegee Airmen, including some who fought in the skies over Italy and the Mediterranean Sea, had proven they could fly just as capably as white pilots. More than 300 Tuskegee Airmen were deployed overseas before the war ended, and 84 gave their lives in World War II. Some of Adams’ classmates later went on to fly in the conflicts in Korea and Vietnam. The Tuskegee Airmen helped pave the way toward the eventual desegregation of the armed forces. President Harry Truman issued an executive order in 1948 officially ending Adams left the Army at the end of his tour and went home to take care of his aging parents. He married his “lady friend,”Barbara Jean, in 1946. They would go on to celebrate 51 years of marriage, raising four sons, until she passed away.

Adams had gone back to his old job as a motion picture projectionist for a movie theater, but to help support his growing family, Adams took on a second job with the Post Office in 1957. “I wanted to be a clerk,” he said, “but I would have had to do night duty.” He couldn’t work at night and keep his job as a projectionist, so he became a letter carrier instead.

Along the way, Adams earned a bachelor’s degree and then a master of fine arts degree in painting and illustration at the Kansas City Art Institute in Kansas City, MO, and started a lawn service business.

Adams began painting portraits for money. He did all this work—carrying the mail, caring for lawns, running projectors and painting—so Barbara Jean could stay home with their children. “I wanted my wife to be at home with the youngsters until they were able to take care of themselves,” he said.

Adams carried mail on a route on the north side of Kansas City that included his home—he reached the post office in five minutes each morning and ate lunch at home each day—until he retired in 1984. “Not everybody wanted that route. It was a rough route—the boxes didn’t all have the names on them,” Adams recalled. “But I loved the route. It was a wonderful route for me. I met a lot of people and made a lot of friends.”

After the war, segregation was still a part of life for Adams, including at his local NALC branch. As was the case with many branches in the southern and border states at the time, the Kansas City branch did not admit black carriers. African-Americans who wanted union representation in those cities often joined either the National Alliance of Postal and Federal Employees—a union that did not discriminate by race—or joined separate NALC branches chartered specifically for black letter carriers. (For more information about the NALC and racial segregation, see NALC’s official history book, Carriers in a Common Cause.)

Adams and some other black carriers managed to join the whites-only branch, while also remaining in the other union, by paying dues but not going to the branch meetings, just to get better benefits.

On the national level, many letter carriers had worked for decades to overturn the national NALC policy that allowed branches to discriminate by race. The issue was finally settled in 1962 when President John F. Kennedy issued an executive order outlawing discrimination by federal employee unions. Black and white letter carriers henceforth would be NALC members, in the same branches. “They were striving to get a union of togetherness, and that’s what they did,” Adams said.

“Once you get together and work with people,” he said, “you don’t have too much difficulty getting along with one another.”

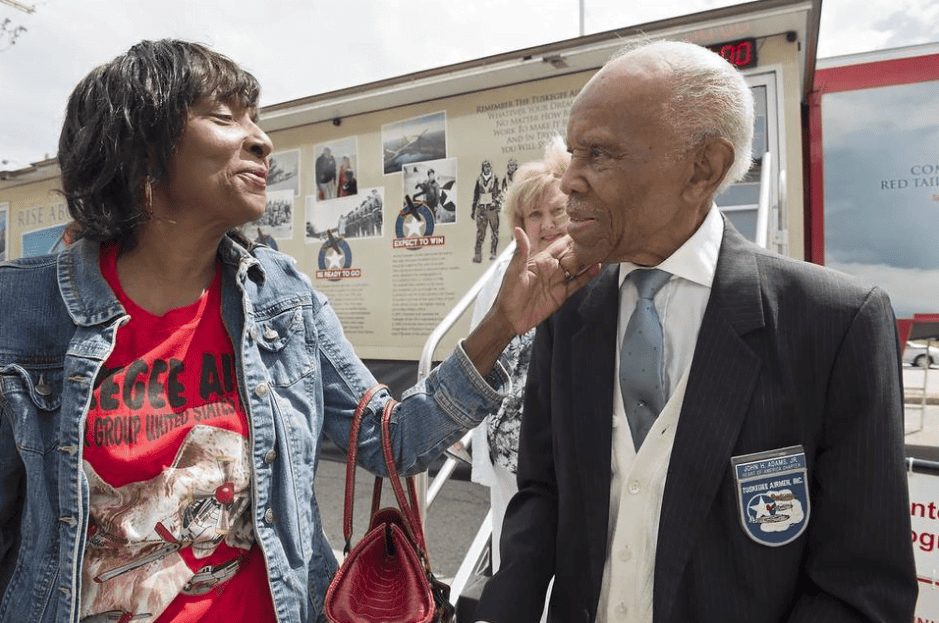

Aug 19, 2015, Adams visiting the RISE ABOVE Traveling Exhibit at the Kansas City Aviation Expo & Air Show.

Listen to Mr. Adams share his reflections of his time as a Tuskegee Airman https://www.star-telegram.com/news/traffic/honkin-mad-blog/article228509914.html

Sources

The CAF Red Tail Squadron is a volunteer-driven organization dedicated to educating audiences across the country about the history and legacy of the Tuskegee Airmen, America’s first black military pilots and their support personnel.