Margaret Anne Cook

Margaret Anne Cook

June 23, 1918 – Sept. 18, 2010

Class 43-W-3 (Trainee)

Margo was born June 23, 1918, in San Antonio, Texas, to Dr. Ernest Dale Cook and Julia Yost Cook. Her family moved to the Los Angeles area in 1925. After graduating from Occidental College in 1939, she began her teaching career.

Margaret Anne Cook, known to her friends in Alaska as “Margo,” was teaching school in Downey, California, in 1941 when she read about female flying Jackie Cochran. “I wanted to do something different,” Margo said. “I liked to be the first to try new things, so I quit teaching job and signed up for the Civilian Pilot Training (CPT) program.” This was the first step towards becoming a Woman Airforce Service Pilot, or WASP.

At the time the government offered this free program, only one in ten trainees could be a woman. Margo acquired her private pilot’s license in June of 1941, but without the minimum of 100 hours in the air, she couldn’t follow Jackie Cochran’s steps and become a WASP. She went to the desert in Blythe, California, where every waking minute she was flying to accumulate the required hours.

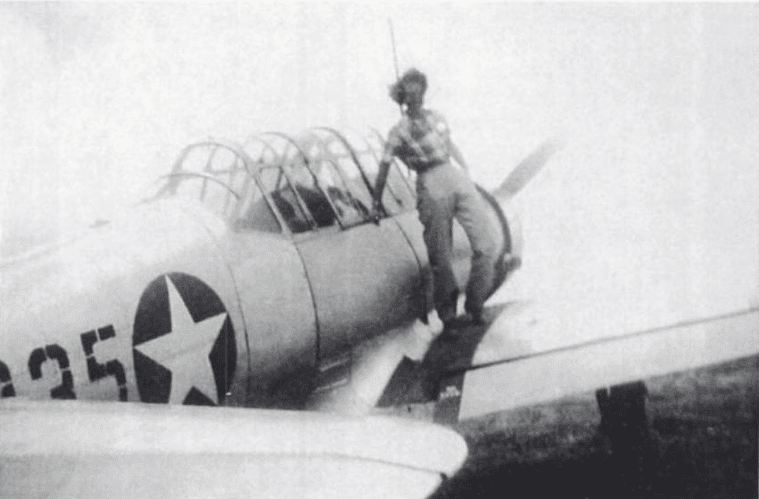

Margo – or “Cookie,” as her classmates nicknamed here – became a WASP in 1943 based in Houston, Texas, where the women had to be housed off base in motels and eat at local cafes and soda fountains. Margo recalled their clothes. “We call them zoot suits. They came in three sizes” large, larger and extra-large. They were basically jumpsuits. They also gave us heavier fleece-lined pants and jackets to wear because we flew open-cockpit BT-17s and when the wind blew – which it always did around Houston – it was very cold. The wind sock always stood straight out.”

Margo completed her primary training, followed by basic training in a Vultee Vibrator, a popular nickname for a plane “that shook a lot.” A few days before Margo’s class was to be transferred to Sweetwater, Texas, where they would be housed at a military base, Margo and her classmates engaged in a softball game. The ball came flying across the field. Margo and a friend

Both chased it, ready to catch it in their mitts. Instead of catching the ball, he women collided, head to head. Unfortunately, this ended Margo’s career in the WASP. Her ear had to be re-attached and she lost her hearing in that ear. Although disappointed, with no severance, or disability pay or benefits, Margo considered this event a turning point for the good.A friend who owned a Taylorcraft that she called Private Willis asked she to fly with her to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. “Every time we touched down, the men would yell that WACS and WAVES were winning the war….They resented women pilots.”

“We flew on to Wayne, Michigan, and my friend asked me to look after a Stinson, which I gladly did,” Margo said. The people at Stinson were impressed with my knowledge and gave me a job as a compass compensator. One day when I was sitting in the cockpit, making the compass adjustments, a young man named Boots came to help me. Before long, they advanced me to a better position – A & E mechanic – and that was fine. Eventually I became the assistant crew chief.”

Margo Cook on a BT-17 or Basic Trainer when she was a WASP in Houston, Texas, in 1943

Margo laughed as she recalled an incident while she was working at Stinson. “I am deathly afraid of bees. I had climbed into the plane and closed the windows, unaware there was a bee inside. As soon as he made his presence known, I shut the engine off and jumped out!”

Margo didn’t dwell on her fear of bees, explaining that she obtained her commercial license in Private Willis and continued to fly to Detroit City Airport where Stinson Aircraft asked her to become a test pilot in their L-5. Her technical experience at Stinson was the ticket to becoming one of the first-known female test pilots in the United States. “As a test pilot I did what is called “squawking” – putting the aircraft through various maneuvers to be sure it was air worthy and didn’t have any problems with the wings or mags, and fly straight and level.” A civilian, she not only flew test runs right off the factory line for the military, she also gave demonstrations and taught herself to do aerobatics. “I lived to fly upside down,” Margo said. “The belly of the plane would be streaked with oil and the crew was not happy about cleaning up the mess. They threatened to make me clean it, and met me with solvent and rags one time when I landed, but I refused.”

Margo was employed and considered herself lucky in December of 1944 when the WASP program ended and her classmates couldn’t find a job flying. Her fiancé was killed in World War II and Margo didn’t pursue marriage again.

Margo talked of stunt flying for a Hop Harrington movie in the Stinson airplane filmed at Thunderbird Field in Phoenix, Arizona. “I had to fly around wearing Hop’s huge hat and when I landed, I’d fall on the floor of the plane and he’d put on the hat and take credit for my efforts. I really thought I was the hero, not him. There were two other pilots, men, and when I found out they were being paid more, I placed a phone call in the middle of the night and demanded equal pay. And I got it.” Margo said, matter-of-factly, “I also acted as a technical advisor on the movie because I had more knowledge than the other pilots.”

Margo could have continued to do movie stunts, but she noticed a lot of pilots had ulcers and weren’t having as much fun flying for other people. She opted for one movie and quit.

“Following the movie work, I was asked to take a Stinson back to Dreyfus, New York, for interior design changes,” Margo said. “I’ll never forget it. The workers couldn’t believe I was flying the bigwigs around – the administrators. When we’d take off, they’d stand on the ground, their fists raised in the air to protest.”

Stinson merged with another company in 1946 and Margo returned to teaching until a former roommate suggested that she should come and teach in the Last Frontier. Margo did some flying at local flight services after she arrived in Alaska, and taught high school and became a counselor. In 1954 when the Alaska Ninety-Nines were created, Margo became a charter member.

Ralph Campbell first met Margo Cook when he and his wife lived in an apartment building in Anchorage where Margo was during the disastrous earthquake of 1964. He was a pilot and often took Margo flying in his Tri-Pacer with a 160-horsepower engine (originally 150 horsepower). “She wrung that plane out!” Campbell said. He explained that meant Margo put the plane through stalls and flew inverted just like she did as a test pilot for Stinson Aircraft. “She made me sit up and take notice! Margo’s one hell of a pilot and I’m not exaggerating. Don’t get me wrong; she’s not a daredevil, she just knows what she’s doing.”

Flying is what made Margo the happiest. “I like to do dangerous stuff like fly just above the trees and buzz farmhouses before I moved to Alaska, “she said. “The farmers would get mad, but it never stopped me. It was fun.”

On one flight, Margo was determined to find a small field where she could land the Stinson L-5, but it seemed to be unrecognizable. She landed at an unknown field and since she was in a military plane without proper identification, she had to wait to be cleared for takeoff. Stinson received a call and confirmed yes, Margo “Cookie” Cook was the pilot authorized to fly the L-5. “When I returned to base, the crew came running outside and hung a big sign around my neck that read ‘Property of Stinson Aircraft. If found please return to Wayne, Michigan,’”

Margo said, “I’ve been very independent all my life. I had two Master’s degrees – one in Science, the other in Guidance Counseling – and my commercial flight instructor’s license.” She retired from Anchorage School District in 1982.

Pat Haller, a member of the Alaska Ninety-Nines, recalled when she took classes from Margo in high school. “She was tough, but she was very good.: Asked if she remembered Margo touting her background as a civilian test pilot or World War II WASP, Haller didn’t recall any time it came up until they reconnected as members of the Ninety-Nines. This was no surprise because Margo doesn’t brag, but she will talk about flying if approached, and her eyes lights up when she shares her story.

Margo continued to fly just for fun at Spernak Airways at Merrill Field in Anchorage, and also helped to schedule the airplanes at Wilbur’s Flight Service, also based at Merrill Field, but her paid flying career ended when she came north in 1953. “My friends in the WASP program continued to pursue flying in the Lower Forty-Eight with the hope of getting to fly into space, but it didn’t materialize,” Margo said. When asked what her goal would be if she were a young woman taking flying lessons today, Margo replied, “I’d want to be an astronaut.”

I wonder if NASA would let Margo do aerobatics with the space shuttle. It’s a sure bet she’d want to put the shuttle through its paces!

Sources:

Thank you for permission granted from Women Pilots of Alaska: 37 Interviews and Profiles © 2005 Sandi Sumner by permission of McFarland & Company, Inc., Box 611, Jefferson NC 28640. www.mcfarlandbooks.com

Texas Women’s University

WWII Women Pilots