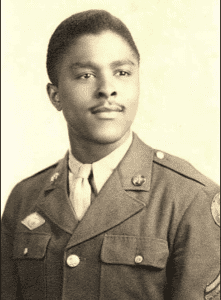

Cpl. Robert D. Holts – Omaha, NE

Cpl. Robert D. Holts – Omaha, NE

1924 – February 12, 2021

Born in 1924 in north Omaha, the son of Robert William and Eunice (Anderson) Holts, he was one of nine children. His father worked as a porter at the Union Outfitting Company at 16th and Jackson streets. Holts was 15 when his mother died.

“Life was hard,” he stated in an interview, “Dad never made much money. If he had made $25 a week, that would have been great.”

These were Depression years and the kids chipped in. In Holts’ case he sold newspapers on the streets in downtown Omaha for four years before working as a busboy at the Blackstone Hotel near 36th and Harney streets.

He attended Kellom Elementary School and Central High School. His years at Kellom, he recalls, gave no hint of racial antagonism. It was his work selling newspapers, and the refusal of storekeepers to give a black newsboy a drink of water, that gave him the first sign.

“I have positive feelings about Kellom,” he said. “All the teachers were white, of course. I never saw a black teacher in all my years there.”

For all that, he never sensed disrespect. That lurked outside, in the adult world.

“Me and my brother were 9 and 10 years old, selling newspapers,” he said. “My brother had a tendency to play with dogs in the street, and one bit him.

“We ran into the police station looking for help and they chased us out. That was when racism showed itself particularly to me.

“I couldn’t get a drink of water at a restaurant at 15th and Farnam. They would send me out. I didn’t understand those things. It was something we had to get used to.”

In November 1942, at the age of 18, he enlisted in the Army Air Corps. There was a draft, but it did not extend to 18-year olds so enlistment was his only route to service. He enlisted in Omaha and was assigned to Jefferson Barracks Military Post at Lemay, Mo., just south of St. Louis, a major center for basic training.

This is Mr. Holts’ account of his time serving in the U.S. Army and being a Tuskegee Airman:

“On November 21, 1942, I enlisted in the United States Army Air Corps, along with five very close friends. We were all still high school students, none of us beyond 18 years of age. There was Joe Carter, (who subsequently became an Air Crew member of the 477th Bombardment Group and an original member of the Tuskegee Airmen); Lincoln Spencer, Robert Goodwin, Leonard Covington, and J. C. Jackson. They are all now deceased except for Leonard.”

Having been sworn in to the service at Fort Crook, Nebraska (now Offutt Air Force Base), we proceeded at once by train to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas; where our uniforms were issued, and where the Army General Classification Testing (A.G.C.T.) was done. Recruits scoring over 110 on the A.G.C.T. tests were qualified for further testing for Officer Candidate School (O.C.S.) or to take the qualifying test for Aviation Cadet Training (A.C.T.). We were not aware of any of those possibilities, and were not told about them.”

“While at Fort Leavenworth for those few days, I began to notice that there were no white recruits in our barracks, but I just dismissed the observation as of no consequence. However, the following week, when we arrived at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, near St. Louis, where our Basic Training was to begin, I was astounded at what I was observing; I had never seen so many Negroes (Blacks, Colored People), concentrated in one place before! And that’s not all. These people were all recruits, Buck Privates, and not an Officer or Black Non-Commissioned Officer on the post that was visible to me! Much later during our thirteen weeks of basic training, I saw a Black Warrant Officer, who was a Chaplain.”

The thirteen weeks of basic training, however, were fun to us because we were so young, and by our being together from childhood, we could handle the drills, obstacle courses, etc., with ease. The Drill Instructors (D.I.), all white, performed much as you can imagine when marching and drilling us. The only hard part was having to endure the cold weather (December) while being outside for long hours at a time. There were times when Leonard or Robert (clowns at heart), would step out of ranks while we were drilling, and would mockingly prance around right behind an unknowing drill instructor, and flow back into the ranks, unobserved. Or they would teasingly respond orally to some kind of statement by the D.I., mocking his syntax without the D.I. being any the wiser. Such impromptu hilarity helped relieve the monotony of the day.”

“The time came for our being separated, in order to pursue our military occupational specialties. Joe and Leonard went to Maryland to an airbase for Auto Mechanics; Lincoln, Robert Goodwin and J.C. went to California to separate engineer outfits. All were overseas in the Pacific Theater by September 1943.”

I was sent to Franklin Technical Institute, in Boston, Massachusetts and was enrolled in an intensive engineering drafting course in January of 1943. We were in class eight hours a day studying drafting and surveying. The surveying in the winter of 1943 in Boston was tough, but I was learning that this was activity to be expected in the Military. We were billeted or housed in a suburb of Boston, in a big stone house near Boston College, a place called Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. It was more like being in college, because we were not on a military post, but just minutes away from downtown Boston. The white soldiers in our class at Franklin Technical Institute were envious of our housing, because they were housed in quarters in downtown Boston more like barracks. I liked our quarters the best, certainly. Our group leader or class leader where we lived, John Adams, subsequently became a Tuskegee Airman (a pilot). One other class member also was successful in the Tuskegee Experience, Cletus Bordeaux from St. Louis, and became a pilot.”

“When the drafting course was completed, I was shipped to an Air Base, Langley Field, Virginia; which is of course near Hampton, Virginia. I was assigned to Company “B”, the 428th Signal Construction Battalion, and was re-introduced to a totally segregated army. It appeared that the mission of the 428th was to install telephone poles and lines in combat zones. I don’t know whether that technique was used for the duration of the conflict or not. My drafting duties were very minimal at that time. I was kept occupied by making organizational charts and graphs, small things like that. Some days I did nothing but hang around the orderly room, helping the clerks, or something.”

“From time to time, I would observe the many types of aircraft that would appear overhead and on the base. It became challenging to me to identify them visually or by sound.”

“It was now mid-summer 1943, time for my first furlough. Still 18 years old, I went home on leave, and was surprised to see Joe Carter there, now 19 years old, wearing wings of an aerial gunner, and involved with the Tuskegee Airmen. Now I knew I was going to take the Aviation Cadet Test.”

“When I returned to the base, I had been promoted to Corporal, and was very interested in flying. I had just learned how to drive a car by driving a jeep on the back roads of the base. One evening I drove a jeep over the Hangar Line, and asked and received permission to ride on a B-24 Liberator Training Flight. The crew, of course was all white, and I didn’t know what my reception would be like; what with the military segregation. They were very friendly, and welcomed me aboard. I could hardly believe it, my first airplane ride and on a B-24, right in the cock pit, with the pilot and co-pilot, looking at the cluster of instruments as they tooled the plane around the sky, over Chesapeake Bay and Virginia. I’ll never forget that experience, especially the touchdown at 120 MPH. The next day I went to Base Headquarters at Langley Field, and took the Aviation Cadet Qualifying Examination and passed it. I was overjoyed!”

“In the meantime, I was still with Company “B” 428th Signal Construction Battalion. It was now about November 1943, and we were on maneuvers at Camp Cumberland, Virginia; living outside in the woods, preparing for overseas duty.”

“I was now 19 years old, and my orders came at the end of December for me to report for Pre-aviation Cadet Training at Keesler Field, Mississippi. Two or three other soldiers, Harry Hackett, Ralph Green and Edward Quander, having successfully passed the test, were also enroute to Keesler Field; so, we shared a drawing room on the train from Virginia to Mississippi. I can’t remember whether we were allowed to go to the dining car or how that was worked out.”

“Keesler Field meant that in addition to the psychological and psycho motive testing that we had to go through, there was more orientation and basic training to go through. Green and Hackett, both college students, failed and were returned to Langley Field. I followed in April, thoroughly morose and dejected.”

“Back at Langley Field, I learned that the Battalion had left the base and were now probably overseas. In 1945, I heard a rumor that the entire outfit was lost. I have never heard any such verification of that fact.”

“Both Harry Hackett and Ralph Green, although washed out as cadets, applied for Infantry O.C.S. and became 2nd Lieutenants. Hackett, after having been mustered out, moved to Detroit with his wife, went to Law School and became a Federal Bankruptcy Referee or Judge.”

“In July of 1945 I was assigned to Goodman Field, Kentucky; where Colonel Benjamin O. Davis Jr., was now the Base Commander. He had recently returned from overseas duty as the leader and Group Commander of the Tuskegee Airmen, 332nd Fighter Group. I was assigned to the 118th Base Unit, Squadron “D”. My specific duties were with the Base Statistical Control section under the leadership of Lt. William T. Coleman Jr., and Lt. Emmet J. Rice. Our responsibilities included amassing all detailed recurring reports vital to the Operations and Training and Logistics of the activities at the Airbase, and transmitting required information to proper sources on a timely basis.”

He was honorably discharged in 1946 and spent most of the years thereafter in Detroit serving as a letter carrier with U.S. Postal Service.

He lived through an era when blacks faced daily humiliation to a point where a black man sits at the pinnacle of social and political power in the White House.

As the honor conferred upon him by the Bellevue City Council demonstrated, along with his induction into the Nebraska Aviation Hall of Fame in 2007, and the Congressional Gold Medal awarded to the Tuskegee Airmen.

“I’m glad those days are over with,” he said. “I hope they are anyway, because there’s more to be said that’s favorable than unfavorable.”

Original Tuskegee Airman Bob Holts enjoyed his RISE ABOVE experience along with the students. September 3-6, 2014

Sources:

Omaha World-Herald

Tuskegee Airmen Alfonza W. Davis Chapter