Roger Cecil Terry

August 13, 1921 – June 11, 2009

Class: 44-K-TE 2/1/1945 2nd Lt. 0841165 Los Angeles, CA

Unit: 477th Bombardment Group

Pilot roster listing

Visit the Virtual Museum to see Roger “Bill” Terry Square

Learn more about the Freeman Field Mutiny

“O for a man who is a man, and, as my neighbor says, has a bone in his back which you cannot pass your hand through!” When Henry David Thoreau shared these words in his 1849 essay Civil Disobedience, he was lamenting the fact that while many people complain about injustice, fewer people are actually willing to risk everything and do something about it. One such man was Roger C. “Bill” Terry who not only served his nation as an officer during World War II, but also a person of conscience who stood up against segregation.

Terry was born August 13, 1921 in Los Angeles. His father Joseph Roger Terry was originally from Texas and was a clerk for the United States Postal Service. Terry’s mother Edith Ross was originally from Mississippi and she was a teacher. Sibling Jack was older, and Dickenson and Joseph were younger. The family lived in the home they owned at 11627 Bandera Avenue in the Compton neighborhood.

After graduating high school, Terry enrolled at the University of California, Los Angeles campus. His roommate was future-baseball great and American hero Jackie Robinson. He graduated at the age 19, harboring dreams of being a pilot and serving his nation.

On November 24, 1943, Terry enlisted in the military at Fort MacArthur in San Pedro, California. He would be accepted into the Tuskegee Airmen training program, graduating with class 44-K-TE on February 1, 1945, earning his wings and commission as a 2nd Lt. Terry was assigned to the historic 477th Bombardment Group, the first bombardment group whose pilots and mechanics were African Americans.

On March 1, 1945, the 477th was moved from Godman Field at Fort Knox, Kentucky to Freeman Field, Seymour, Indiana in anticipation of overseas operations set to begin during the summer. While the structural limitations at Godman Field had made for difficult bomber training for the 477th, the sociological limitations at Freeman Field would prove challenging.

Despite the military ordering the desegregation of recreational facilities about two years before the 477th arrived at Freeman Field, Terry and his fellow Tuskegee Airmen and support staff found segregation nonetheless. According to Black History Untold Stories, the 477th was told during their initial briefing that: “This is not the time for blacks to fight for equal rights or personal advantages. They should prove themselves in combat first. There will be no race problem here, for I will not tolerate any mixing of the races. Anyone who protests will be classed as an agitator, sought out, and dealt with accordingly. This is my base and, as long as I am in command, there will be no social mixing of the white and colored officers.” This resulted in recreational facilities, including the officer’s club, PX or postal exchange, and theater, being segregated.

According to newspaper accounts of the time, Freeman Field was able to segregate despite the military ban because the reason for the separation given was, “The army operates recreational facilities on stations with the point of view of obtaining the highest degree of moral and efficiency among all members of the command.” Leaning on the idea that there is long tradition of separating students and instructors during recreational time and that similar policies existed at other facilities, Freeman Field commanders argued that it was “unwise” to blend students and teachers while off-duty. The practical result of this however at Freeman Field was that the division between instructors and trainees was really the difference between white and black officers and staff. Ironically, at some of these same bases and fields, enemy prisoners of war could use American military recreational facilities that were denied to African American officers of the United States. As a symbol of the unfair nature of the policy, some members of the 477th called the officers’ club designated for “students” only “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

On April 1, 1945, a letter carrying the order to maintain separate recreational facilities was distributed at Freeman Field. 2nd Lt. Terry and other officers thought the order unfair and illegal considering the military’s ban on segregating such facilities. On April 5, 1945, the group from the 477th went to the officer’s club with goal of entering and being served as was their right. That action would be known as the “Freeman Field Mutiny” and in many ways, served as the beginning of the modern Civil Rights era in the United States.

Some officers there that day think that perhaps a mole got word to base commanders Major General Frank O’Driscoll Hunter and Colonel Robert R. Selway Jr. that a protest would occur. As the officers arrived at the officer’s club, they were met by the provost marshal and other guards. Upon trying to enter the club, 2nd Lt. Terry “jostled” 1st Lt. Joseph D. Rogers – in essence, by brushing against him to pass through the doorway. A total of 61 African American officers were arrested and confined to quarters until disposition occurred for the offense. Soon after, officers were directly ordered to sign a document certifying that they read, understood, and would abide the regulations about the segregated recreational facilities. 101 African American officers refused, many because they felt that signing the document was the same as agreeing to the unfair and discriminatory policy. These officers were then arrested.

In part because of media coverage and pressure from groups like the NAACP, most of the officers were released with letters of reprimand added to their files by General Hunter. Decades later in newspaper accounts, these officers would discuss how those letters affected their ability to properly advance in the military and how they harmed them.

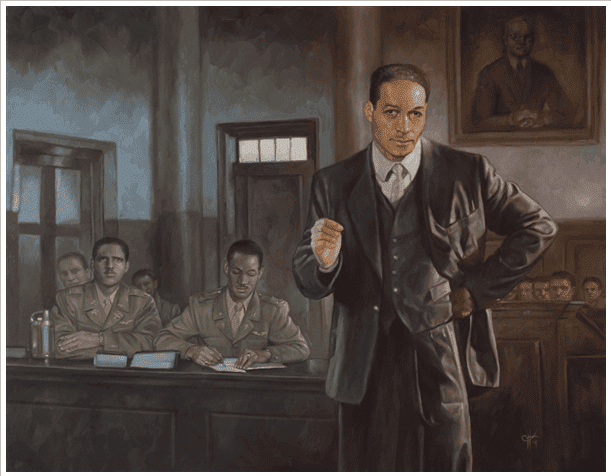

Three of the officers involved in the protests, 2nd Lts. Terry, Mardsen A. Thompson, and Shirley R. Clinton, were kept under solitary confinement and eventually tried under a general court martial with charges brought by Col. Selway during the first week of July 1945 at Goodman Field. The original presiding officer of the court martial was Benjamin O. Davis, but because of a procedural protest raised, he was replaced by Captain George L. Knox. Terry, Thompson, and Clinton’s defense was lead by future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. The trio was acquitted, except for a single charge against 2nd Lt. Terry who was found guilty of “jostling” a superior officer. The brushing against 1st Lt. Rogers was defined by the court as an act of violence. Nearly two years after his original enlistment date, Terry lost the command of his B-25 bomber and was discharged from the military during November 1945.

“The Trial Of Roger Terry” Artwork depicting the trial resulting from the Freeman Field Mutiny. By artist Chris Hopkins

The effects of the court martial were severe, both militarily and as a civilian. Terry would never fly a combat mission overseas or achieve his dream of being a military pilot. His conviction required him to identify himself as a felon on job applications or school records. Despite graduating Southwestern Law School in 1949, his conviction affected his ability to earn his law license.

Terry did not let the challenge go unmet, however. He found ways to contribute to society. On June 24, 1949, he married Anna Mae Williston, and the couple had two sons. He had a career as a Los Angeles County district attorney investigator and Probation investigator. In 1972, Terry helped found the Tuskegee Airmen, Inc., a group dedicated to preserving the history and contributions of the Tuskegee Airmen and support staff.

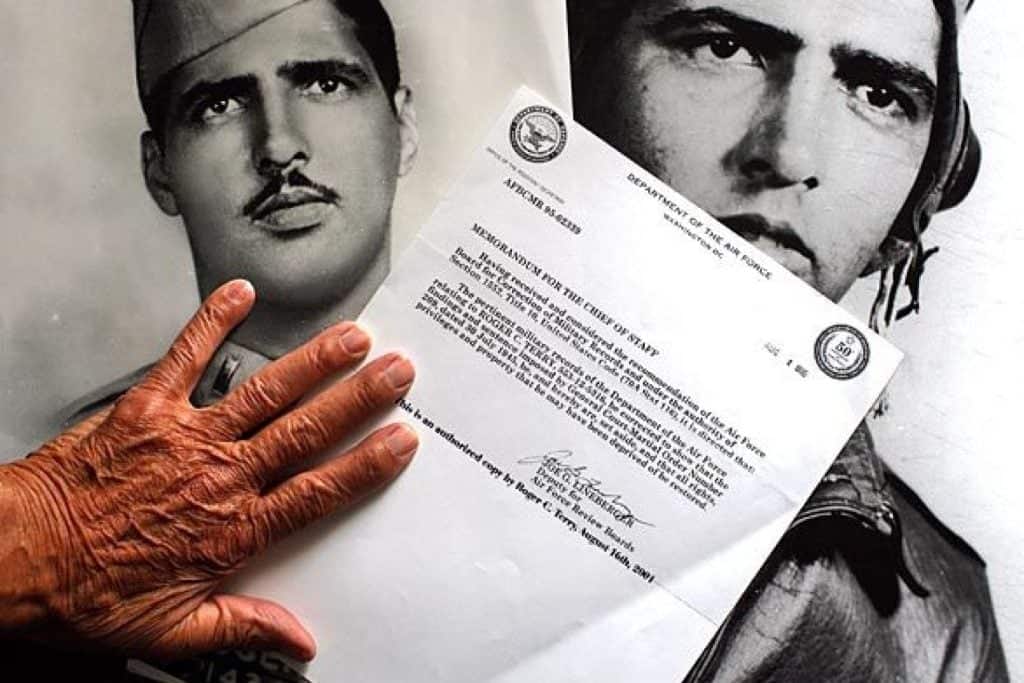

August 2, 1995, would see the long-standing injustices that occurred at Freeman Field corrected. The Air Force removed the letters of reprimand from the files of those affected upon request and review, and Terry’s rank was restored, fine returned, and record expunged. While the pardon could never erase the 87 days spent in solitary confinement or the 50 years of damage that followed, 2nd Lt. Terry said, “For the first time in 50 years, I could vote, I could hold office, I was restored Second Lieutenant, and it only goes to show that we’re a nation of laws. If you wait long enough, you will be vindicated. The only thing is that they wasted so much money and so much time doing it. But we did show them that we could fly.”

As more and more people learned of the stand against prejudice that 2nd Lt. Terry and his fellow officers took back in 1945, honors finally began to be earned. On August 16, 1997, for example, those involved in the “Freeman Field Mutiny,” including Terry, returned for the first time to the same location where the protests took place.There, they were honored by Seymour Mayor John Burkhart. In 2007, Terry was among those who were awarded the group Congressional Gold Medal by President George W. Bush for their service to the nation and to the cause of equality. 2nd Lt. Terry was even invited on a tour of the Lucasfilm vaults and got to see and hold many props from famous George Lucas films like Star Wars and Indiana Jones. Although his health at the time prevented him from attending, 2nd Lt. Terry was among the Tuskegee Airmen invited to the inauguration of President Barack Obama. About six months later, on June 11, 2009, Roger Terry passed away.

“We were young (and) we were right,” Roger Terry told the Los Angeles Times in 1995. By his act of conscience and by his service, 2nd Lt. Terry helped begin much more than he could have imagined on that April 1945 evening. He helped begin the process that made more real the American ideal that all people are equal.

Sources:

- 1930 United States Census.

- 1940 United States Census.

- Ancestry.com. U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com, 2005.

- California Department of Health and Welfare. California Vital Records.

- Findagrave.com. Photo credit: BJW.

- Franklin, Ron. “Roger C. Terry: A Tuskegee Airman Sacrifices His Career For Justice.” Black History Untold Stories

- “One Year Ago: Roger “Bill” Terry.” Los Angeles Times

- Newspapers.com

- “Roger “Bill” Terry Obituary. Los Angeles Times

- The National Archives in St. Louis, Missouri; St. Louis, Missouri; WWII Draft Registration Cards for California, 10/16/1940 – 03/31/1947; Record Group: Records of the Selective Service System, 147; Box: 1790

Written and submitted by Nick Tenuto

Learn more about the Freeman Field Mutiny at

- Freeman Field Mutiny

- The Freeman Field Mutiny and Tuskegee Airmen Beyond Alabama

- “Tuskegee Airmen History: The Freeman Field Mutiny” by Ronald E. Franklin

The CAF Red Tail Squadron is a volunteer-driven organization dedicated to educating audiences across the country about the history and legacy of the Tuskegee Airmen, America’s first black military pilots and their support personnel. Learn more at www.redtail.org.