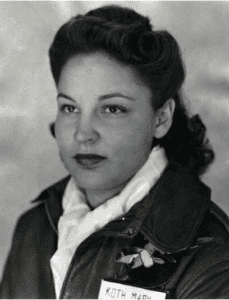

Susie Winston Bain

Susie Winston Bain

July 21, 1922 – February 3, 2017

Class W-44-4

Training Location: Avenger Field (Sweetwater, Tex.)

Assigned Bases: Love Field (Dallas, Tex.) and Laredo Army Air Base (Tex.)

Planes flown: PT-17, BT-13, AT-6, B-26, P-40 and P-63

Susie Winston Bain was born on July 21, 1922 in Markham, Texas a little town about nine miles from Bay City Texas.

On Dec. 7, 1941, Susie was returning to her University of Texas dormitory after a sorority meeting when she heard about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Like other students, she wanted to serve her country. At the start of the war, not many military jobs were open to women. Bain made up her mind to fly with the Women Airforce Service Pilots.

“I really wanted to make some contribution to the war effort,” Bain says. “If Rosie the Riveter could rivet, why couldn’t I fly?”

The Bay City native quit college for financial reasons and then took a grinding job as a typist to save up money. She asked her boss to increase her salary from $85 a month to $95 so she could take the flying lessons required to qualify as WASP trainee.

“Pilots were desperately needed to take care of home jobs and release male pilots for overseas,” recalls Bain, who now lives in Austin. “He tried to assure me that a woman’s place was in the home, not the cockpit of a plane, but he would give me the extra $10 if I promised to give up this ‘tomfoolery.’ I declined his offer, worked a little harder, ate a little less and finally reached the 35 hours necessary to enter flight school at Sweetwater.”

Bain tells this story while threading her way through an exhibit about the WASP service, “Flygirls of World War II,” on view at the Bullock Texas State History Museum through Feb. 8. Organized by the Wings Across America research project, the show relies on interviews with dozens of women like Bain who served in multiple capacities between 1942 and 1944.

Right off, it documents the initial opposition to women flyers.

“This is not a time when women should be patient,” first lady Eleanor Roosevelt said on Sept. 1, 1942. “We are in a war and we need to fight it with all our ability and every weapon possible. Women pilots, in this particular case, are a weapon waiting to be used.”

More than tough enough

The first item that Bain — eyes flashing with moxie and good humor — encounters at the exhibit is a WASP uniform. The pilots at Sweetwater wore white shirts and khaki slacks, but graduated in the Santiago blue uniforms. Alongside the full-sized model is a WASP doll in a crisp diminutive uniform.

Bain could not afford to buy her own uniform, although she wore one during graduation. The WASP service was disbanded in 1944 in order to give jobs to male pilots returning from the European theater. It was not until 1977 that they received veteran status. They waited until 2010 to receive the Congressional Gold Medal of Honor for their service.

During the war, Henry “Hap” Arnold spearheaded support for the WASP program within the armed forces. Pioneering pilot Jacqueline Cochran founded and directed the forces.

More than 25,000 women volunteered; 1,830 licensed pilots were accepted into the experimental flight-training program. Of those, 1,704 graduated. They received the same long training — on the ground and in the air — as male pilots.

“I expected to fly off into the clouds with a long white silver scarf floating out behind me,” WASP Doris Brinker Tanner told an interviewer in 2000. “Wasn’t that way, kiddo! We worked like dogs in dirty, greasy coveralls. We had to break down an engine. We had some tough ground school classes, but oh, the flying was so wonderful!”

They started training at Houston Municipal Airport — now Houston Hobby Airport — then moved to Avenger Field in West Texas after a few months. Its wooden barracks came with bays that held six cots, six lockers, two tables and six chairs each. Two showers, two sinks and two commodes served each pair of bays.

“Sweetwater was full of snakes, spiders, desert and dust storms,” Bain says. “All of which I experienced with little enthusiasm physically. Once, a dust storm covered the field and I was forced to fly in circles. I couldn’t find the runway. Fortunately, my gasoline held up until the storm abated, and I got ‘home’ safely. Whew!”

After she graduated and flew military planes regularly, she was forced down into a cabbage field in Louisiana during a storm. Bain overheard the farmer calling in the incident by phone.

“The plane just came down in my field,” she recalls him saying. “The pilots are coming this way. Wait, those aren’t pilots. They’re women.”

Although Bain says most men in the service were very nice, she sometimes faced skepticism or even undisguised contempt from male counterparts. In Laredo, she co-piloted a B-26 that towed targets for gunners in a B-17.

“I was receiving lots of back talk from those training for gunnery school,” Bain says. “They’d say: ‘You stupid (expletive) WASP! Can’t you keep your plane steady so I can hit the target?’ I was tempted to say that I doubted if the Nazis would accommodate him by making the target more available.”

The last WASP class graduated on Dec. 7, 1944. Thirteen days later, the service was disbanded, with “no honors, no benefits and few thanks.” They paid their own way home, Bain confirms.

“When I got out of the plane, the ground crew all came out, and they hugged me,” WASP Betty Tackberry Blake recalled in 2001. “We all shed a few tears. I patted the plane. I knew I’d never get in one again. I was heartbroken.”

At least women had proved that they could operate just about anything and accomplish their dreams.

“If another national emergency arises – let us hope it does not, but let us this time face the possibility — if it does, we will not again look upon a women’s flying organization as experimental,” Gen. Arnold said on Dec. 7, 1944. “We will know they can handle our fastest fighters, our heaviest bombers; we will know that they are capable of ferrying, target towing, flying training, test flying and the countless other activities which you have proved you can do.”

Not unlike college women of the time, who were assumed to be seeking a “Mrs.” degree, Bain discovered that people thought WASP servicewomen like herself really wanted to “catch a male pilot.”

“I often wondered how we could have managed to log 60 million air miles if all we ever did was ‘flirt’ with the boys.”

Susie Winston Bain (2nd from right) poses with four fellow WASPs by a car, circa 1944. The women wear the early WASP trainee uniform of a white blouse, khaki trousers, and A-2 leather jacket with Fifinella patch

Sources:

Austin American- Statesman, Michael Barnes

Texas Women’s University in Denton, Texas

Gateway