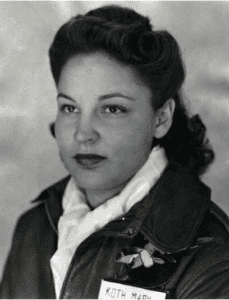

Flight Officer

Flight Officer

Class 45-C-SE 5/23/1945 Flt. Officer T69972 Richmond, VA

November 1, 1925 – October 4, 2019

Before 1940, Black people were barred from flying for the U.S. military, Bailey said, but becoming a pilot was always his dream.

“In high school, I used to watch the planes go across the sky until they were out of sight,” Winston-Salem native Bailey said. “I told myself, ‘One day, I’m going to fly myself a plane.'”

The opportunity came when Bailey was 17 and stumbled upon an advertisement in the newspaper for the Tuskegee Airmen.

Although his parents begged him not to go, he knew it was what he was meant to do, he said. He was sent to Mississippi for testing before he was selected to go to the Tuskegee Army Air Field (TAAF) in Tuskegee, Alabama, to learn to fly.

“It was fantastic and it was exciting,” Bailey said of his time as a Tuskegee Airman. “I was never afraid, just eager.”

Bailey logged hundreds of hours while training for two years and two months to be a fighter pilot of a single-engine plane.

At the beginning of his training, he had a few close calls, nearly crashing into a B-25 twin-engine bomber plane and once the ground after the plane spun out. But he was eager and a quick learner, he said. “Everything you could do with a plane, they made sure we could do it,” he said, “all the acrobatics.”

But within two weeks of being certified, World War II had ended. Bailey was told he could stay in the Army, but they would take his flying license away, he said.

It was a story of disbelief that echoed among the ranks of Tuskegee pilots who returned home. After years of fighting the enemies of World War II, they had never anticipated the battle that waited for them at home.

Instead of being welcomed as heroes, the pilots were shunned and stripped of their right to fly. African-Americans were not allowed to become commercial pilots for nearly 20 years afterward, he said.

Bailey’s parents prodded him into going to school at the Hampton Institute where he studied auto mechanics. But in the midst of a racially tense and divided America, he was unable to secure a job as a mechanic, becoming a post office courier in 1952.

“I was prepared to go overseas, but the war was over,” he said. “Being a (commercial) pilot was out of the question. The post office was the only place that would hire me.” In the years that followed, Bailey never got the chance to become a pilot again, but never lost his love for planes.

In February 2012 Bailey visited the RISE ABOVE Traveling Exhibit at the Transportation Museum in Spencer, NC where he signed autographs, shook hands, told stories, and reminisced about his days as one of the original Tuskegee Airman.

In February 2012 Bailey visited the RISE ABOVE Traveling Exhibit at the Transportation Museum in Spencer, NC where he signed autographs, shook hands, told stories, and reminisced about his days as one of the original Tuskegee Airman.

We salute you, Sir! History lives on through the wisdom and stories of those who paved the way for the world today.

Resources:

North Carolina Transportation Museum

The CAF Red Tail Squadron is a volunteer-driven organization dedicated to educating audiences across the country about the history and legacy of the Tuskegee Airmen, America’s first black military pilots and their support personnel.