“Just as the black pilots proved that they could fly military aircraft in combat as well as the white pilots, so did the black weather personnel prove that they could perform meteorological functions as well as the white officers.”

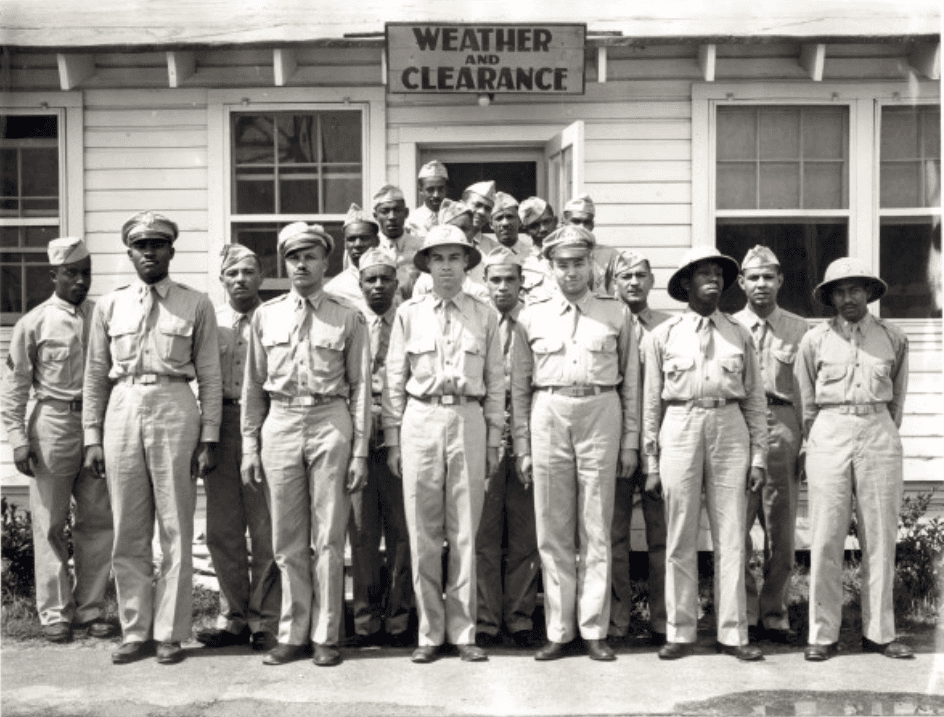

The Tuskegee Weather Detachment formed on March 21, 1942. (Photo/United States Air Force)

During World War II, at a time when people of color were breaking into military areas and roles previously denied to them, a group of African-American United States Army Air Corps servicemen became what were likely the first black meteorologists.

Leaders of the Army Air Forces were hesitant to utilize African Americans in the period of military buildup leading up to the war, as Air Corps officers lacked confidence in their flying abilities.

“During the 1940s, there had been so much resistance against African Americans being in the Air Force, at first,” said Dr. Molefi Asante, author of “African-American History: A Journey of Liberation and the African-American People,” and professor and chair of Temple University’s Department of Africology and African-American Studies.

Pressure placed on the War Department from black organizations led to the department pressing the Air Corps, resulting in the Army Air Forces opening up their units to black members.

Throughout the war, flexibility increased in accepting blacks into the Army Air Forces, and “at the end of 1942, there were thousands of black soldiers, whereas there were none the previous year,” and their numbers increased to more than 145,000 by June 1944 in a force of more than 2 million men, according to author Alan Osur.

In 1939, President Franklin Roosevelt authorized the nationwide Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP), which allowed college-aged students to learn what it took to become a pilot. Roosevelt authorized the program to accept black students who then trained at historically black colleges and institutions, according to the National Park Service.

The military remained racially segregated during the war. While the training of African Americans to fill enlisted observer and forecaster roles first began in March of 1941 at Chanute Field, Illinois, according to the Air Force Weather History Office, black pilots eventually received their basic training at Tuskegee Field in Alabama.

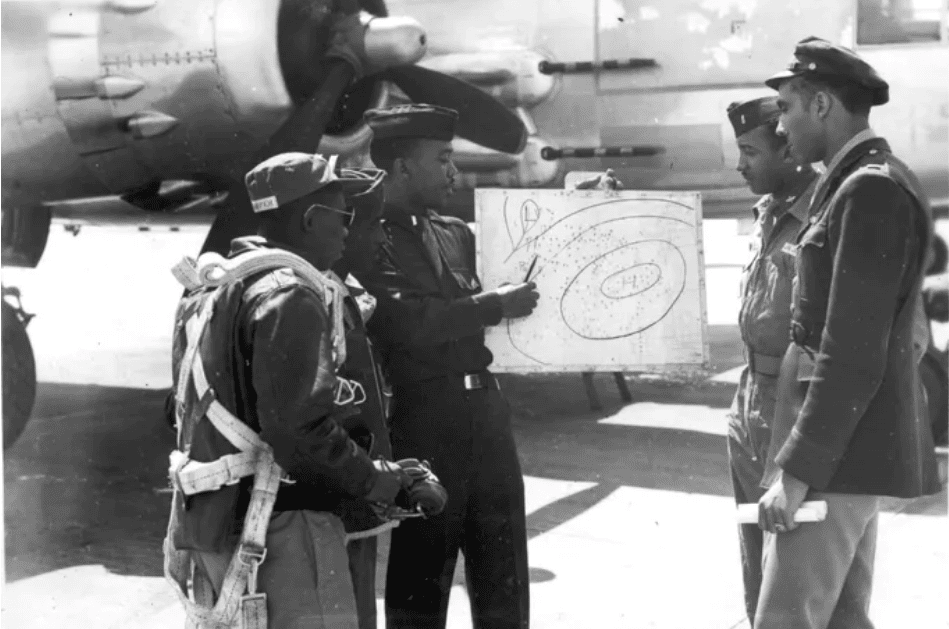

Lt. John Willis briefs a B-25 aircrew before a mission in the summer of 1945. More than 50 African Americans served as weather forecasters and observers, while more than 10 served as meteorological aviation officers during World War II. (Photo/United States Air Force, 557th Weather Wing)

The air and crew personnel associated with the Army Air Forces’ black flying units were called the Tuskegee Airmen. The group comprised the first black pilots to fight for the U.S. during the Second World War.

The Tuskegee Weather Detachment, made up of 15 men, formed on March 21, 1942, originally organized as part of the Tuskegee Army Flying School, according to the American Institute of Physics.

Tuskegee was chosen for black military pilot training in part because the Tuskegee Institute had already begun training African-American civilian pilots, according to TuskegeeAirmen.org. Also, “the region had more days of good flying weather than many other parts of the country, and the area already had a segregated environment, which was consistent with the segregated training.”

Why Black history is critical to the future of science

The Tuskegee weathermen totaled just 0.2 percent of all weather officers, a percentage that “greatly underrepresented the black population as a whole or even those who served in the Army Air Forces,” wrote author Gerald A. White Jr.

“If you’re a pilot, you want to have excellent, precise weather data,” said Asante, noting that the racial tensions were a concern of the Tuskegee Airmen.

“Many of the African-American pilots preferred to have African-American weathermen who would give them the most precise information about flight paths and so forth,” Asante told AccuWeather.

In order to qualify for the detachment, the men had to complete and pass rigorous testing and challenging coursework, according to the American Institute of Physics.

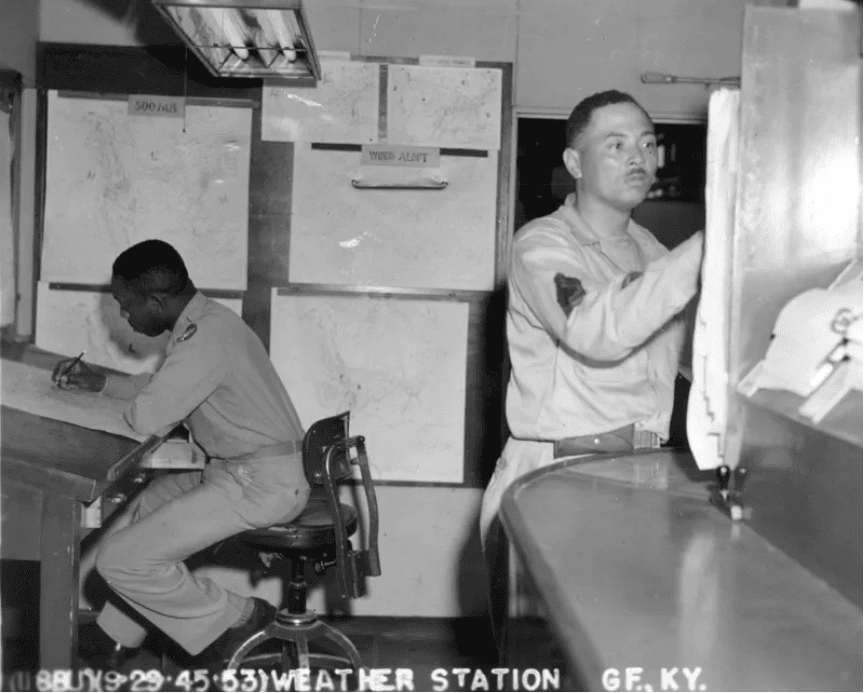

Two observers prepare a forecast in the weather office in Godman Field, Kentucky, in 1945. (Photo/United States Air Force, 557th Weather Wing)

Because the weather forecasters had to draw their maps by hand, and due to the precision, that was necessary, many of them became experts at illustration and mapmaking, according to Asante.

One of the notable figures of the Tuskegee Weather Detachment was Wallace Patillo Reed, who was first black meteorologist in the military as well as possibly the first African-American meteorologist in the Weather Bureau, according to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

In February of 1942, Reed graduated from a specialized training course at MIT, which was one of a few institutions that hosted cadet programs from which cadet graduates were recruited.

“Reed was so important that he became the leader and trainer for [the group of] African-American weather people,” Asante said. “I think he had never received the attention that he should’ve received for being the pivot point for African Americans, opening up a door for a lot of people in the profession of meteorology.”

Tuskegee Airmen served with distinction in combat, according to the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force, helping to contribute to the eventual integration of the U.S. armed services, which went into effect on July 26, 1948. On this date, President Harry Truman signed an executive order that abolished segregation in the armed forces.

“The Tuskegee fliers’ sort of demonstrated what was possible, and the meteorologists demonstrated that the people who are able to give pilots the science of meteorology were also useful and gave them lots of security in the skills and ability to fly,” Asante said.

Tuskegee served as the primary school of instruction for African-American pilots until its closure in 1946.

Source:

Accuweather.com, by Ashley Williams, AccuWeather staff writer