Black cadets for the new segregated military flight training program didn’t just show up at Moton Field in Tuskegee, Alabama one day. The runup to “opening day” involved a lot of work by others before the first class of 13 could get off the ground in the summer of 1941.

Once the decision was made to set up the new flight school in Tuskegee, a training airfield had to be built. The contract to build the airfield and initial buildings went to Alexander & Repass, an Iowa firm that was owned by a black engineer and contractor named Archie A. Alexander. Construction at Moton started in the summer of 1941, just about the time that the first class of cadets class were starting classroom training. The company had a deadline to complete the project, but heavy rain and bad drainage affected the workers’ ability to grade the airfield and construct the outbuildings. Students and others at the Tuskegee Institute stepped up and helped the workers out so that the aviation training facility could open in the fall of 1941 as scheduled.

The new facility was named for Dr. Robert R. Moton, the second president of the Tuskegee Institute (Booker T. Washington was the first). Dr. Moton retired in 1935 after 20 years as T.I. president; he died in 1940. He had been a strong proponent of offering aeronautical training at T.I. and the programs he helped develop resulted in T.I. being the only black educational entity approved to offer the Civilian Flight Training Program. Having the CFTP active at T.I. was directly related to Tuskegee being chosen for the flight training program that produced the Tuskegee Airmen.

Interestingly, the runways at Moton Field were not paved – they were grass. Given the wear that the runways got – remember that each cadet got 60 hours of flight training at Moton; that’s a LOT of takeoffs and landings! – they became rutted which affected how the students’ airplanes behaved (see last week’s blog entry about some airplanes breaking!).

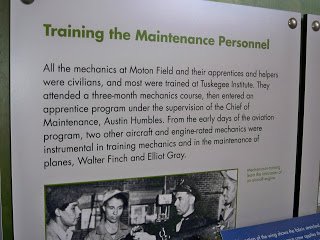

When the Stearman P-17 biplanes got to Moton, people had to be ready to maintain them, no matter if the problem was airframe or mechanical in nature. Any delay in keeping the planes airworthy would negatively affect the cadets’ progress through the program. This meant that mechanics had to be trained at Tuskegee.

The mechanics were required to use their own tools so entering the Tuskegee mechanics training program meant a financial commitment up front. Many women – all black – also completed the airplane mechanics program at Tuskegee. They got just as greasy and worked just as hard as the male mechanics did.

This picture gives a good idea of how the mechanics worked on every part of the airplane.

As mentioned previously, the airplanes took a beating as newby pilots learned to fly. ALL supplies were requisitioned from the USAAF, including new wings and other airplane parts. The Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site museum has a special display that shows how the mechanics tried to repair a damaged wing before having to requisition a new one.

A special shed on the grounds held the compound – called “dope” – that was used to rebuild wings (see center section of the wing above to get an idea of what it looked like after the dope was applied – I was reminded of duct tape, but it wasn’t nearly that easy to work with).

While the field was being built, flight instructors were hired or assigned to the Tuskegee program. Many were military, but some were not. Many were black, but some were not. Fortunately, all were motivated. The Site features information about many of the flight instructors who worked with the Tuskegee program, and their credentials are impressive. Like the majority of WWII pilot candidates, many of the Tuskegee cadets came into the program with no previous flight experience so the instructors played a key role in their success.

Next week, the final entry in this series will cover what the cadets at Tuskegee had to learn in order to become U.S. military aviators. HINT: It wasn’t just about the flying.

The RISE ABOVE Traveling Exhibit Is Still Doing the “Howdy All y’All” Thing in Texas

The Traveling Exhibit is still welcoming visitors at the 1940 Air Terminal Museum at Hobby Airport in Houston today and tomorrow. Hours are 1o a.m. to 5 p.m. daily.

Next Tuesday through Saturday, the Traveling Exhibit will be at the Cavanaugh Flight Museum in Addison, Texas. Hours are 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. each day.

The CAF Red Tail Squadron is volunteer-driven 501c3 organization that operates as part of the Commemorative Air Force. For more information about the Squadron and its educational mission, visit www.redtail.0rg.

www.redtail.org