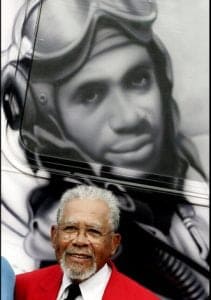

Yenwith K. Whitney

Yenwith K. Whitney

December 22, 1924 – April 12, 2011

Class 44-F-SE

Unit 301st Fighter Squadron.

“I wasn’t concerned about what anyone thought about me. Flying was a challenge and something I wanted to do. I wanted to be a valuable asset to our country. I wanted to be a good soldier.”

When 18-year-old New Yorker Yenwith Whitney was sent to Tuskegee, AL, for military training in 1943, he was entering several new worlds. First, he was leaving childhood to join the military in wartime. Second, he was learning to fly, then an unlikely dream for African Americans. Third, the young black man from the Bronx was joining an all-black community for the first time.

“My first real experience with black kids was living in the army air corps,” Whitney said. “It was my first profound exposure to being part of a group that was exclusively black.” Whitney’s parents had moved to a suburban neighborhood for better schools and safer streets in the 1920s, so Whitney grew up going to a predominantly white school and local church.

Growing up, he loved to tinker with mechanical things and was delighted to receive a model-airplane kit for a birthday. He built the plane, flew it, and promptly fell in love with flying. But “it never crossed my mind that I could be a pilot. That was an impossibility.”

Yet war needs intervened. The Army Air Corps began training black military pilots at Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute and nearby Tuskegee Army Air Field in 1941. Whitney applied for and was ecstatic when he was accepted for pilot training. Joining the group that later became famous as the Tuskegee Airmen was one of the highlights of his life. “We were very close,” he said. “It was a life and death experience.”

Whitney’s life had changed profoundly. “I went into the Army Air Corps and did something I wanted to do tremendously-I wanted to fly-and I was successful. That set me apart in both black and white society. And that had a tremendous impact on me.”

He was assigned to the 301st Fighter Squadron. It was one of four all-black fighter units in the 332nd — the 99th, 100th, 301st and 302nd — of the 15th Air Force.

“When we arrived in Italy, they were flying P-51 Mustangs. The P-51 was the most gorgeous and the best fighter the 15th Air Force had,” he said with a smile. “I got a brand new one that I named ‘Lovely Lady,’ for my mother on one side, and ‘Terri,’ for my girlfriend on the other side.

“When we flew our first mission, my feet were shaking on the rudder pedals,” he remembered. “If we weren’t sharp, we were told someone was going to shoot us down. That mission went off pretty well. We escorted bombers to Austria.”

“When we flew our first mission, my feet were shaking on the rudder pedals,” he remembered. “If we weren’t sharp, we were told someone was going to shoot us down. That mission went off pretty well. We escorted bombers to Austria.”

It was their job to stop the German fighters from attacking the American bombers. The pilots of the 332nd Fighter Group were good at it.

To emphasize how the pilots of the 332nd were appreciated by the bomber crews, he read a letter he received from a crewman following another speech he gave recently about the Tuskegee Airmen.

“It seems to me the 332nd usually flew on the longest missions with us,” the crewman wrote. “It was reassuring they accompanied us all the way to our missions and back. When we learned the 332nd was providing our escort, we breathed a little easier.

“Thank you again for those great deeds more than half a century ago,” the old crewman said in part.

“On March 24, 1945, we flew the longest mission on the European Continent. We flew from Italy to Berlin and back. It was an all-out effort on the part of the 8th Air Force, 15th Air Force, 12th Air Force, and 9th Air Force,” Whitney noted. “The bombers were dropping one last devastating blow on Berlin. I was on that mission flying bomber escort in my P-51.”

It was on this mission he saw his first German ME-262 jet fighter. The fighter flew by their formation of Mustangs at 500 mph, almost 200 mph faster than their P-51s could fly.

“On that day, the Germans flew every jet they had against us. The war was almost over and they were making their last stand,” he said. “Three of our guys shot down three of the ME-262s that day.”

His unit would receive the Presidential Unit Citation for their part in the last big bomb raid over Berlin.

By the time the war in Europe concluded on May 8, 1945, Lt. Yenwith Whitney had flown 34 missions in a P-51 over enemy territory and was awarded the Air Medal with three Oak Leaf Clusters. Although he never had the opportunity to shoot down an enemy plane, it wasn’t for lack of trying.

Yenwith Whitney poses with members of his squad, who called themselves the Lucky Seven. They were part of 44F Tuskegee Airmen.

Whitney, who flew a single-engine fighter plane, was the youngest in his class at the age of 18. Whitney is pictured at top, second from right.

Shortly after he was discharged from the U.S. Army Air Force in 1945, he applied for a pilot’s job with one of the airlines in New York. He wasn’t considered for the position. The 20-year-old black aviator from Brooklyn found out in a hurry some things in the United States of America hadn’t changed despite the war. It would be 1963 before the airlines hired their first black pilot, Whitney said.

He wanted to study engineering and worked hard to pass the MIT entrance exam. His acceptance to the Institute was another turning point in his life.

Whitney translated his love of flying into aeronautical engineering studies and earned his bachelor’s in 1949. He worked first for Republic Aircraft on stress analysis, then for EDO on structural design of aircraft floats. With his wife, Muriel, he made a decision to venture into another new world.

“In 1956, at our church, I heard about the need for math and science teachers in Africa. I wasn’t particularly enchanted with working on aircraft floats at that time. So, I said to my wife, who was working in the New York City Welfare Department, Why don’t we go to Africa?’ And she said, Okay.”’

The Whitney’s spent a year and a half in a Paris suburb learning French. Then in 1958, they and their two young daughters headed for the strife-ridden French colony of Cameroon as missionaries for the Presbyterian Church. The Whitney’s taught at the first school in that nation that provided secondary education for African boys and girls. And their daughters Saundra and Karen attended the mission school during the difficult civil-war years. When the country became independent in 1961, some of Dr. Whitney’s students became the political leaders of the young, independent nation of Cameroon.

In 1967, the family returned to New York, and Whitney continued working for the United Presbyterian Church in minority education and international education, in the U.S. and Asia as well as Africa. In 1980 he was appointed liaison with Africa, in which capacity he worked with local churches, councils, schools, and hospitals in more than 20 African countries. During his 35 years with the church, he earned a master’s degree in math education and a doctorate in international education from Columbia University.

After his retirement in 1992, Whitney moved to Sarasota, FL, with his wife Lorenza, whom he married after his first wife died in 1978. His participation in church affairs and MIT activities remains extensive. For the church, he has led study tours to Malawi, Madagascar, and South Africa. He also co-led a six-week series on Racism and White Privilege at the First Presbyterian Church in Sarasota and wrote articles on Africa for the national church’s World Update.

For MIT, he has served on the board of directors of the MIT Club of Southwest Florida, as an educational counselor, and as president of the Black Alumni Association of MIT, more commonly referred to as Bamit (bamit.org).

“When I went to MIT, I was well treated and had a good experience in the dormitory, the fraternity, and in intramural sports,” he said. “Yet there were only three other black students when I was at MIT, which is why I became so interested in Bamit. I think Bamit is a very important part of MIT and extremely important for black students.” Organized in the 1970s, Bamit provides professional and personal growth opportunities for African-American students and alumni.

Yenwith Whitney, like a lot of MIT alumni, has followed his own path to achieve his goals. From the historic accomplishments serving as a Tuskegee Airman to his volunteerism for both the Institute and his neighborhood church, Yenwith Whitney led a life that made a difference.

Sources:

Don Moores War Tales

Legacy.com

Wikipedia