May 10, 1923 – September 17th, 2007

Born and raised in Wildwood, FL, Donald Lang trained at the Tuskegee Army Airbase after enlisting in September, 1942. He took flight instruction from C. Alfred “Chief” Anderson, the chief flight instructor of the initial Civilian Pilot Training Program at Tuskegee and also worked with the base commander, Noel Parrish.

Assigned to the 2143D Army Air Force Base Unit, Lang remained at Tuskegee for his entire military career, leaving the Army in February, 1946, with the rank of Sergeant Major. He was awarded three medals: the American Campaign medal, the Good Conduct Medal and the WWII Victory medal.

Brad Lang

Thank you to his son, Brad Lang, for sharing this article he wrote in 2016 for the AIR & SPACE MAGAZINE:

My Father, the Tuskegee Airmen, and the Dream of Flight

An African-American airline captain reflects on the legacy of his forebears.

I knew I would fly for a living by the time I was 14 Years old. I briefly took the controls of a Cessna during an air-taxi flight and, exhilarated, thought I can do this. By that point, flying had already become a central interest of my childhood. When I was very young, in 1970s New Jersey, I had been fascinated by the raptors circling overhead hunting for food, and I pursued radio-controlled models almost as soon as I knew what they were. But even as a child with dreams of flight, a flying career hadn’t crossed my mind until I flew that Cessna. I had never seen or even heard of a black commercial pilot.

Airplanes hold no opinions about who is at the controls, but people have held strong ones. Only in 1963, after a legal battle and Supreme Court decision, did airlines begin hiring African-American pilots. In the 1970s, there were still very few black pilots. Even after it became illegal to do so, black applicants were excluded because of their skin color. Today, it’s far more common to see a person of color or a woman at the controls of an airliner. But of approximately 81,000 commercial pilots in the United States, only about 1,600 (2 percent) are African-American. I’m fortunate enough to be one of them.

Today I fly Boeing 757s and 767s for a major airline. For enjoyment, I fly a North American T-6 Texan, and I’ve also been a flight instructor, aerobatics pilot, warbird pilot, even a classic radio-controlled model flier. Aviation has provided me with a great career and a supportive community—aviators and aviation enthusiasts just seem to instantly understand one another—so I am disappointed to see so few black kids joining that community. And yet I understand the perspective that nearly kept me from an aviation career: I don’t see anyone who looks like me doing this. Why would I think it’s possible for me? My father’s love of aviation was an inspiration.

My father, Donald W. Lang Sr., enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1942. His Army aptitude test showed him to be a good candidate for flight training, but while the services trained white pilots as fast as they could, my dad and other qualified African-Americans had to wait for a precious spot at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. It wasn’t until 1945, as the war in Europe came to a close and the United States prepared for a potential invasion of Japan, that my father was finally sent to flight school in Tuskegee. He logged just under 20 hours in a PT-13D Stearman but did not complete flight training. Instead, he worked as support staff on the ground, eventually reaching sergeant major, the highest enlisted rank. His experience at Tuskegee was not one of combat or deployment, but he was proud to serve his nation, and he carried the Army’s discipline with him for the rest of his life.

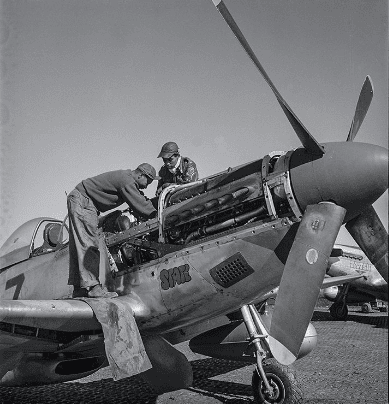

Often forgotten are the maintenance, staffer, instructors, and other who made the flights possible

My father experienced racial prejudice in Alabama, but it was so unremarkable to a black man raised in Harlem and rural Florida that it rarely featured in his stories from the time. I know that he and his friends seldom wandered far from their base; outside its confines, black men could be killed for anything from violating the segregationist Jim Crow laws to simply being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Although Tuskegee is known today for its black pilots, each of them was supported by at least 10 other soldiers, both black and white men: flight instructors, maintenance men, logistics personnel, administrators, commanders—all are Tuskegee Airmen equally and deserve the same regard. But even within the units there was strict segregation, and black personnel were often treated differently than white personnel. As my father and his peers told it, they never got used to the segregation and inequality, but they accepted it as simply a fact of life.

For most Tuskegee Airmen, the end of the war meant the end of flying careers. Airlines kept plenty of white World War II veterans in the air, but only a single Tuskegee Airman made it to the airlines: Robert Ashby was hired by Frontier Airlines in 1965 after he retired from the military.

After the war ended, my father worked at two full-time jobs simultaneously, one at the Newark Housing Authority, the other at the Newark Airport’s post office. He rarely spoke of his experiences at Tuskegee—he did not advertise or expect others to be interested in them. And he never seriously considered pouring his hard-earned money into flight lessons; he didn’t believe they would create opportunities for our family. But he remained interested in flight. Many Sundays after church, he brought my brother and me to Newark Airport—then as now an extremely busy place—and we sat in our car and watched airplanes from all over the world land, while he explained what we were seeing: Those are the flaps, that’s the landing gear, here’s the approach path…. Those trips to Newark kick-started my own fascination with aviation.

The military integrated in 1948, but prejudice didn’t simply disappear, nor did it evaporate from society after the civil rights landmarks of the 1960s. When my family bought a house in West Orange, New Jersey, in 1970, around 40 of our future neighbors signed a petition to stop us from moving in. We moved in anyway. I, like any other black kid, could tell a thousand stories about the insults I suffered growing up, the fights I was forced into, the exclusion I encountered because of my complexion. But like my father and his friends, I saw it simply as a part of life, something to be worked around.

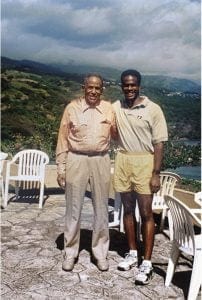

Brad and his father on vacation in Tahiti in 1997

I was about 13 when my father and I bought our first radio-controlled model aircraft, and my quiet father suddenly became the ultimate authority on building and flying, relating every move I made with the RC airplane to what he had done in the Stearman. He talked about feeling the restrained power of the trainer as he taxied to the runway, the sensation of gently pulling back on the stick and lifting off, the unique beauty of the earth from up high. And for the first time he began to tell me about his Tuskegee experiences outside the cockpit: how in sweltering Alabama, black Tuskegee personnel weren’t allowed to use the all-white swimming pool, and when they requested one of their own, a ditch was dug in the dirt and filled with water; how black upperclassmen hazed the younger students by making them do things like hold rocks outstretched in their hands. Soon after, I got to fly that Cessna air taxi and decided I’d find a way to fly. I worked a series of summer jobs: electrician’s apprentice, short-order cook, train station janitor—anything that would help me save a few bucks—then started flying lessons at Flanders Valley Airport in New Jersey. My father gave me advice based on his own flight experiences, and more than once I laughed at his insistence that I build up my calf muscles for proper rudder control, critical to controlling a Stearman but not the Cessnas I then flew. He told his Tuskegee friends—Thomas Tindall, George Wanamaker, and Bill Broadwater—that I was aiming for a job with the airlines. They all encouraged me, as did my uncle Joseph Scott, a Montford Marine (an all-black unit trained in North Carolina). In 1977, just before my high school graduation and shortly before I soloed, I wrote a letter to my future self, saying essentially: Good luck with your new life as an airline pilot. On the envelope I wrote, “Do not open until hired.”

I earned my private pilot’s license at the local airport near my college, Beloit, in Wisconsin. But the college didn’t have a commercial flight program, so I transferred to Purdue University in Indiana. There I earned my flight instructor’s rating and taught flying to build hours until an airline would hire me. I was the only black student in Purdue’s flight program at the time; according to an alumni profile, there were only four others as of 2011. Two years after graduation, Atlantic Southeast Airlines hired me to fly Embraer EMB-110s out of Macon, Georgia. Of the 500-odd pilots at ASA, only five were African-American. I rarely saw the other black pilots because they were based elsewhere, but one of them—an older, more experienced pilot—told me not to be surprised if some white pilots didn’t want to fly with me. His advice was to become a captain as quickly as possible, to build as much time as quickly as possible, to make sure I followed the regulations—and to make sure I knew them well enough that I was always on solid ground before I raised them with a captain who may not be inclined to listen to me. That’s good advice for any pilot, but especially important for me. For the most part the pilots at ASA were professionals, and I never felt treated differently.

The passengers were another matter: People regularly expressed surprise at seeing a black pilot. Almost every black airline pilot I’ve met has many stories about passengers making racist comments. My response was to not dwell on passengers’ opinions and to do the job. I was just happy to be flying.

In 1988 I accepted an offer from Delta Air Lines to be a 727 flight engineer and finally opened my self-addressed letter. I began flying the McDonnell Douglas MD-80 before I moved through the ranks and through ever bigger airplanes to the Boeing 757s and 767s I now fly.

I sometimes wonder if I’d be a captain for a major airline today had I not been exposed to the experiences of my father and his Tuskegee friends. In the difficult and still-ongoing conversation over skin color and discrimination, I hope we can include the group that helped break down so many barriers and light the way for black aviators. That’s why I became part of what’s now the Commemorative Air Force. As a member of the CAF Red Tail Squadron, based in southern Minnesota, I helped restore and now fly a P-51C Mustang painted in Tuskegee colors; at the time of its restoration, it was the only flying airplane to commemorate the Tuskegee Airmen (today there are five). Our B-25, Miss Mitchell, flew from North Africa during the war, and on one or two occasions was actually escorted by the Tuskegee Airmen.

Our squadron’s RISE ABOVE Traveling Exhibit, is on the road nine months out of the year to tell the Tuskegee story. It seats about 40 students, and on a good day we see about 300 total. Often the display meets up with the Mustang at airshows, but it travels mainly to schools. Many times, if a surviving Tuskegee Airman lives nearby, we invite him to come out to tell his story; these days, only about half those we invite are well enough to attend.

Not long ago I flew a Stearman for the first time, the same type my father flew, the airplane in which nearly all Tuskegee pilots learned to fly. It was a clear day when we lifted off from Zamperini Field in Los Angeles, and the airplane was everything my father said it was—lumbering, noisy, and elegant—and much simpler to fly than the airliners I ordinarily log hours in. Whether I am flying a Stearman, a 767, or the Red Tail Mustang, I am thankful for all the moments and stories my father shared about his Tuskegee experiences. And I am encouraged that there are greater opportunities for African-Americans in aviation. The recently opened National Museum of African American History and Culture has selected a Stearman to represent the Tuskegee experience, a small but crucial part of African-American history. I encourage everyone to visit the Smithsonian display to learn about this important chapter.

Brad at the controls of the Commemorative Air Force’s P-51C Mustang “Tuskegee Airmen”. Photo courtesy Jeff Berlin