LTC Frederick Emmanuel Hutchins, Sr.

LTC Frederick Emmanuel Hutchins, Sr.

September 16, 1920 – June 10, 1991

Class: 43-D-SE

Graduation Date: April 29, 1943

Unit: 332nd Fighter Group, 302nd Fighter Squadron

Service # 0-801171

Capt. Freddie E. Hutchins assigned the same nickname to each of his planes: “Little Freddie.” By the end of World War II, Hutchins was flying his fourth “Little Freddie.”

Hutchins of Donaldsonville, Georgia., graduated from flight training on April 29, 1943, at Tuskegee Army Air Field in Alabama. In December, he deployed to Italy with the 302nd Fighter Squadron, part of the 332nd Fighter Group. The 302nd Fighter Squadron flew its first combat mission on Feb. 5, 1944.

On July 18, Lt. Lee A. Archer scored his first aerial victory credit. Several months later, after Archer shot down three enemy planes in a single day, the July 18 credit was changed to a shared credit between Archer and Hutchins. Many believe the credit was changed to prevent Archer from qualifying as the first black ace, a distinction awarded to any pilot who has shot down five or more enemy planes. Hutchins did shoot at the Messerschmitt 109 plane on July 18, but said he did so after Archer had brought the plane down. Several years later, the official record was changed to give Archer full credit for the kill.

Hutchins collected a full aerial credit a few weeks later. On July 26, 1944, 61 P-51 Mustangs left Ramitelli Air Field in Italy for bomber escort missions to Vienna, Austria. Several enemy planes were spotted on the trip, but they remained out of range until the B-24 bombers attacked their target.

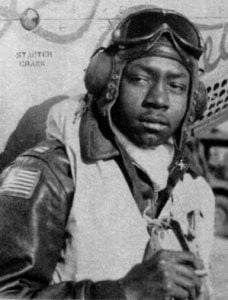

Capt. Freddie E. Hutchins was awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal and Purple Heart. He also is wearing ribbons for each medal under the European/African/Middle Eastern campaign ribbon. Photo courtesy of Craig Huntly

“We were escorting B-24s to Vienna when I got my second (enemy) plane,” Capt. Leonard M. Jackson later said in an interview published in “The Tuskegee Airmen: The Men Who Changed a Nation” by Charles E. Francis and Adolph Caso. Jackson had already collected one aerial victory on Feb. 7. “Capt. Edward Toppins was leading my flight when we sighted three (Focke-Wulf) 190s 10 minutes before reaching the target. Capt. Toppins turned into them and fired, but they were out of range for effective shooting. Toppins damaged one on the tail of the formation, then we reassembled in battle formation.

“Just then we sighted three ME-109s above us making vapor trails. We were at 28,000 feet. We climbed as the ME-109s started a gradual climbing turn. I knew Capt. Toppins was not going to let them get away, so I prepared for a good fight.”

Toppins, Jackson, 1st Lt. Hutchins and 2nd Lt. Roger Romine were each credited with one aerial victory. It was Toppins’ fourth kill.

Hutchins collected his next kills on Aug. 30 when pilots discovered enemy aircrafts under stacks of hay at Grosswardein airfield in Romania. After 15 passes, 46 pilots were credited with 83 kills: Hutchins was credited with four.

The 332nd Fighter Group was sent on strafing missions to three Greek airfields on Oct. 6. The 302nd Fighter Squadron was sent to Megara, but found the base mostly abandoned. As the pilots fired on the base, Hutchins’s plane was raked by anti-aircraft fire, or flak.

“We were just approaching the target and I was flying with Lt. (James) Wilson on his first mission,” Hutchins later said, which Francis printed in his book. “As we approached the target run, I told Wilson to start his run. However, it being Wilson’s first mission, he became excited and was slow in opening up his plane. This retarded my run and cut down my speed. As I pulled up off the target, I was hit by a volley of flak. I looked to my right and saw that my right-wing tip was torn off completely. Looking back, I noticed my tail assembly was practically shot apart. At this time, flak was hitting my ship pretty consistently. I scooted down into my seat to get protection of the armored plates, but just at this time a volley of flak burst through the floor of my plane and struck my leg.

“I called Capt. Dudley Watson, our flight leader, and told him that my plane had been damaged badly and that I couldn’t stay up long. At the same time, by some miracle, I continued to gain altitude. I headed for friendly territory — or rather, a clear spot.

“I managed to clear a mountain peak by a few inches and then my plane began to lose altitude. I was now headed for some trees in a valley. I had very little control, but managed to miss the trees and crash-landed into a small opening.”

Lt. Roger Romine saw smoke from Hutchins’ plane, but could not get a response on the radio. He saw Hutchins’s crash.

“He crashed nose up, disappearing into a cloud of dust about two miles in board on very rocky, hilly ground along the edge of a river gulley,” Romine wrote in a military report. “On my second pass the dust had settled, allowing me to see the fuselage, sitting upright, motorless, wingless and tailless. … The canopy was missing. Peasants were gathering around the plane, waving at me as I passed each time, trying to give me a message. They had something under a treee, around which (another) 50 people were gathered. With flaps lowered and moving at 150 mph, I could see that the plane body was in good shape, the people were very jubilent and evident Lt. Hutchins was unconscious but alive.”

The Greeks pulled Hutchins from what was left of his plane.

“When I came to, I found myself sitting at my controls with the engine of my plane lying several hundred feet away,” Hutchins said. “My goggles were smashed on my forehead. My head was aching and my legs felt like they were broken. However, after examining my legs I found that they were all right except a deep flak wound on my left leg.

“I was pulled out of my ship by some Greeks who arrived at my plane shortly after it crashed. I walked a few steps, then passed out. Some men raised me up and began to walk me around. Then they put me on a donkey and walked that donkey around in a circle. They did this to restore my respiration. However my back hurt me so badly I begged them to stop. I was then carried to a doctor who rubbed my back with some homemade olive oil, strapped me up and put me to bed.

“The fleas had a wonderful time off me that night. The next day, I decided I couldn’t live through another such night so I made plans to leave, though I was still in pain. I was taken into the city. There I gained transportation back to the base.”

Hutchins returned to Ramatelli on Oct. 23.

By the end of the year, Hutchins was promoted to captain. He later served in the Korean War and the Vietnam War. Hutchins was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, an Air Medal with four oak leaf clusters and a Purple Heart for his military service.

Sources:

The CAF Red Tail Squadron is a volunteer-driven organization dedicated to educating audiences across the country about the history and legacy of the Tuskegee Airmen, America’s first black military pilots and their support personnel.