2d Lt Walter Peyton Manning

2d Lt Walter Peyton Manning

May 3, 1920 – April 1, 1945

Class 44-D-SE

Graduation Date: April 15, 1944

Unit: 332nd Fighter Group, 301st Fighter Squadron

Lt. Walter P. Manning and Flight Officer William P. Armstrong were killed during a dogfight over Austria in 1945. Manning of Philadelphia graduated from flight training on April 15, 1944, at Tuskegee Army Air Field in Alabama. He soon deployed to Italy with the 301st Fighter Squadron, part of the 332nd Fighter Group.

On April 1, the 332nd Fighter Group successfully escorted B-24 bombers to a marshaling yard at St. Polten, Austria. On the return trip to Ramitelli Air Field in Italy, the group spotted enemy planes south of Wels, Austria.

“After fulfilling our mission, the 301st broke away from the rest of the group and flew straight down the Danube River,” Flight Officer James H. Fischer said in an interview included in “Tuskegee Airmen: The Men Who Changed a Nation” by Charles E. Francis. “We found nothing of interest in the Danube area, but when we got to Linz we met a great deal of flak. Frankly, we were looking for enemy barges on the river, but instead sighted enemy planes.”

A battle ensued. Seven pilots shot down 12 enemy planes, including a German FW-190 shot down by Manning, but Manning and Armstrong were killed.

In a military report, 2nd Lt. John E. Edwards said he saw one of the group’s P-51 Mustang hit by fire from an enemy plane, and dive to the ground.

“I also observed a pilot bail out of his plane after having been attacked by enemy fighters about 15 miles south of Wels,” Edwards wrote. ” I was not able to identify either of the pilots or the planes, except that they were our planes in both instances. It is logical to assume that either 2nd Lt. Walter P. Manning was the pilot that spun in and Flight Officer William P. Armstrong was the pilot that bailed out or vice versa since two of our eight planes that engaged in the fight didn’t return.

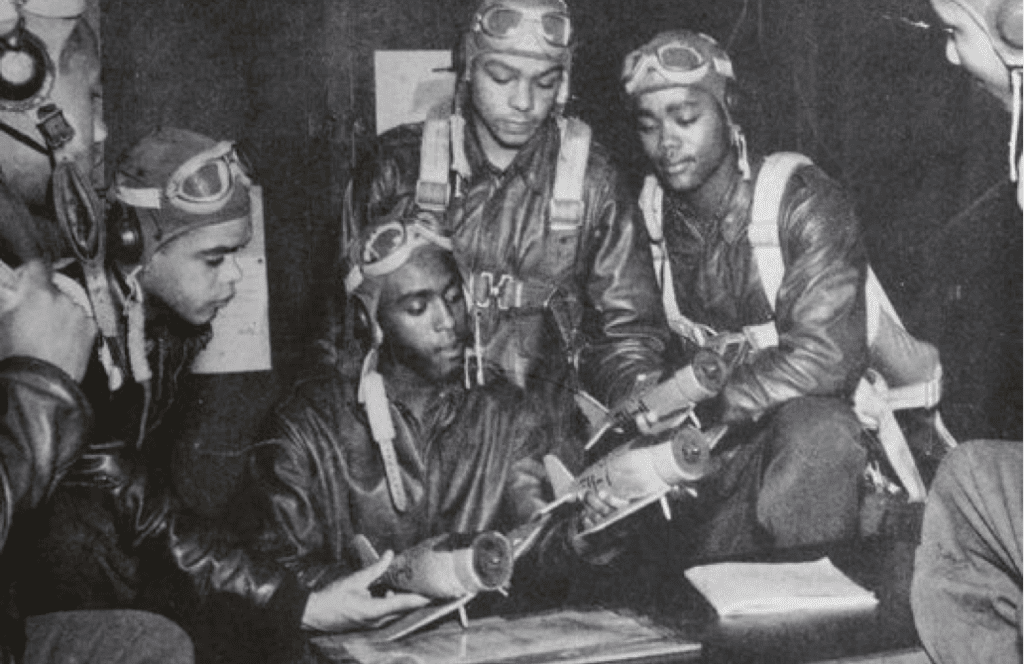

Tuskegee Airman Walter Manning, center, with several other pilots looking over model P51 Mustangs in Alabama

On the morning of April 3, 1945, Second Lt. Walter P. Manning of West Philadelphia sat in a jail cell at a Nazi air force base in Austria.

The doomed fighter pilot, battered and beaten, wore his wings on his collar. He was a proud Tuskegee Airman, a member of country’s first black combat aviation unit. Back in Philly, Manning had gained attention for his dedication to his dream of becoming a flier: He had failed his physical exam because of a hammer toe and could have avoided war. Instead, he used his defense-plant salary to pay for surgery – so he could fly.

“That’s real patriotism,” read a headline in one of the local African American newspapers.

Now, he had escaped death twice in the last two days. First, when he bailed out of his plane after a dogfight, where he’d taken out a German fighter. Then, when he was lynched on April 3, 1945.

He had flown more than 50 missions, and six times was awarded the Air Medal for heroism. He had a fiancée, whose picture he kept close. He was not yet 25.

The lynching of Lt. Manning, the only black flier known to have been hanged in Austria during World War II, was never enshrined in museums, let alone noted in the day’s newspapers.

In a war that shaped the American consciousness, there are still shamefully forgotten horrors. And this one is particularly chilling because it drew on the sins of our own past.

“Isn’t it striking that the Germans monitored the lynching of African Americans in the South of the United States and set loose a similar kind of violence against black airmen?” said Georg Hoffmann, an Austrian-based historian who has researched Manning’s murder. In 2016, Hoffmann and fellow researcher Nicole-Melanie Goll created a database of the 9,000 Allied pilots killed or shot down over Austria, unearthing details on the fates of many fallen crews.

Seventy years after the war, the historians were the first to focus on the terrifying and largely forgotten Nazi phenomenon of Fliegerlynchjustiz. With the air war all but lost by 1943, the Nazis incited citizens to kill any captured Allied pilots. The historians discovered 150 Allied pilots – 101 Americans – who were murdered on the ground, most by civilians. White fliers got beatings or bullets. Manning got a rope.

“The reason was the propaganda,” Hoffmann said. “The Americans are doing this to African Americans, we should do the same.”

The historians’ work led the Austrian and U.S. governments to mark the spot where the Philadelphia pilot was lynched with a memorial stone in a service attended by high-ranking U.S. military officials. It was a solemn, elaborate event with honor guards, military bands – and a flyover.

“He was a young man who desperately tried to overcome racism in the United States – who became a pilot when it was not for someone of his race to do it – and then died the way he died,” Hoffmann said. “We wanted to commemorate him.”

“He wanted to fly in the worst way.”

Harry Stewart, then a lieutenant in the 301st Fighter Squadron, flew alongside Manning that Easter morning in 1945. They had been together at the Tuskegee Institute, the Alabama university where black pilots trained. He remembered his friend as outgoing and affable – a powerful swimmer who did laps in the institute’s Olympic-size pool.

“He wanted to fly,” Stewart remembered, “in the worst way.”

To avoid the racism of the Jim Crow South, the men stuck to the campus canteens and dances.

“If I could help it, I did not put myself in the path of humiliation,” said Stewart, who is 93, a retired engineer who lives in Michigan with his wife of over 70 years, Delphine.

At a cadet graduate ball, Manning danced to the beat of Count Basie with Dicey Thomas, a pretty university student, who wore a white dress and pinned her hair up in the style of the day. The two were engaged before Manning shipped out.

In the dogfight that Easter morning over the Danube River, Manning and Stewart and five other Tuskegee men, flying their distinctive red-tailed P51s, took out a dozen German fighters. After his plane was struck, Manning ejected, drifting slowly down in his chute toward the forming mob.

An unmarked grave

When the Austrian historians began researching Manning’s death, they found many of the details of his prewar life had long faded. With the help of Jerry Whiting, a retired California police officer-turned-Tuskegee researcher, they filled in what they could.

He was born in Baltimore but raised in Philly. He attended Howard University but did not graduate. By 1942, when he tried to enlist with the Army Air Force, he was living with his mother, Winifred, in West Powelton and working as a machinist at the Signal Corps Depot in Germantown. On his mental examination, he scored 119 out 150, when only an 83 was needed to qualify as a flier. He was accepted into the service the year after his toe surgery.

The American military investigation into Manning’s death was quickly closed, Hoffmann found.

American liberators soon discovered his body in a shallow grave near the air base. A compassionate civilian had marked the spot with a wooden cross. His body was moved to a soldiers’ cemetery in France.

Suspects were identified, including two German officers, believed to be part of the Werwolf, a Nazi guerrilla group pledging to fight on even as the Allies advanced. The officers allegedly bound Manning’s arms behind his back, delivered him to the crowd, and hung a sign around his corpse, reading: “We defend ourselves.”

No one was ever tried. It’s hard, Hoffmann says, not to think that race played a role in the case’s being scuttled – a final insult to Walter Manning.

“Nobody ever tried to put together what happened,” Hoffmann said. Nobody, that is, until the Austrians.

On a sun-streaked afternoon earlier this month, Harry Stewart stood at the Linz Hoersching Air Base, on the spot where his brave friend was murdered. The old pilot offered a sharp salute. And as the ceremony went on, the honor guards marched, and the bands played, and the planes roared overheard, he was filled with emotion at the honor paid to his friend.

“This was a son of Philadelphia,” Stewart said. “If this son of Philadelphia could be recognized so far away for the sacrifice he made for this nation, then I hope that in some way he could be memorialized back home.”

Manning is buried at the Lorraine American Cemetery and Memorial in France. According to a government database, he was awarded an Air Medal with five oak leaf clusters and a Purple Heart for his military service.

Web update, December 14, 2021

Thank you to Jerry Whiting, along with Austrians Georg Hoffman and Nicole Goll, for bringing factual information of the event referring to “the mob” waiting to take Lt. Manning from the jail in Horsching. There was no mob involved. It occurred in the late night/early morning hours and it’s likely there were only two men involved, both Luftwaffe officers with false papers. For years they investigated this case, trying to find the men if they were still alive, unsuccessfully. At this point in the war many of the air force groups had political officers, who were not pilots. Their role was to incite the men to keep the war going and to persuade the men to keep fighting.

Here is the information clarified that is often misrepresented:

- After completion of their escort mission, several members of the 301st Squadron received permission to separate from the group and search for “targets of opportunity” along the Danube River. Their escort mission was completed.

- During the early morning hours of April 3, 1945 (3:30AM) two Luftwaffe officers presented forged orders to the jailer at the Horsching Air Base where Manning was detained, ordering Manning’s release into their custody. The jailer released Manning, as stated in the orders. The next morning Manning was found hanging from a nearby light pole.

- There is no evidence that Manning was “delivered to a crowd”. This was during the early morning hours. In the factual evidence, the two Luftwaffe officers were named. The available evidence suggests that these officers were not pilots, but political officers assigned to the group. From all of the interviews conducted at the time, there is no evidence that there was a “mob” or any other observers.

- Within just days after Manning’s death the 27th Fighter Wing was disbanded, with many of its ranks being sent to the Russian Front in the final days of the war. The case was closed in mid-1947, a year and a half after it had begun, without the two known perpetrators having been found. It’s unknown if they survived the war. Many similar cases were closed about this time.

Sources:

Inquirer.com

Saint Louis Post-Dispatch